African Art in an Art Museum

Edited by Nichole N. Bridges

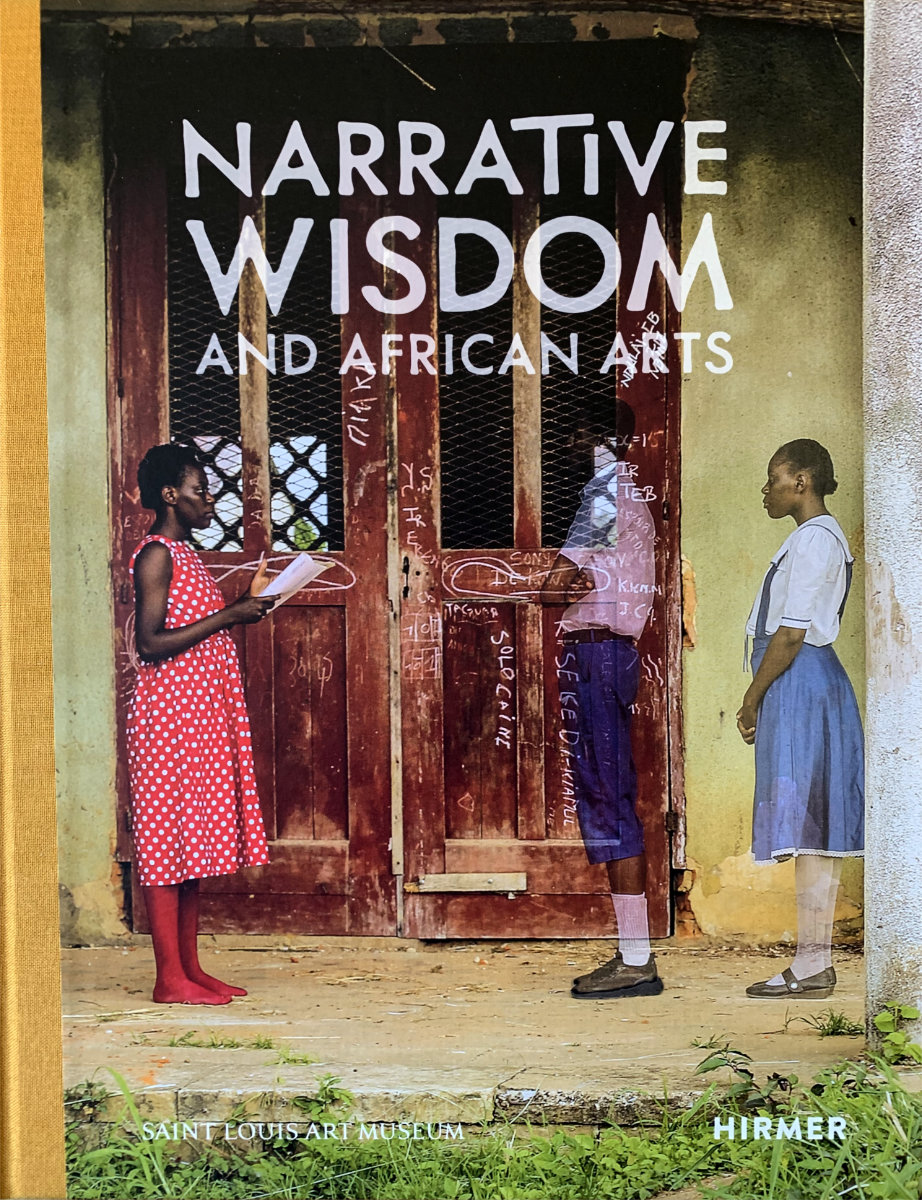

The catalog of the exhibition “Narrative Wisdom and African Arts” by the Saint Louis Art Museum in the United States of America. The exhibition commenced in October of the previous year and concluded on February 16, 2025.

The exhibition’s accompanying catalog, published by the Saint Louis Museum in St. Louis, Missouri, USA, and the German company “Hirmer” from Munich, offers a comprehensive exploration of the intersection of narrative, African arts, and global cultural expression. The volume is under the editorship of Nichole N. Bridges. The book is 240 pages in length and features a visually appealing layout and artistic design, including pull-out pages. The publication is structured into 13 chapters, which are further divided into three overarching categories: “TEMP/ORALITIES; LEADERS; DESTINIES.

The exhibition at the Saint Louis Art Museum in the United States of America connects traditional with modern African art using narration as a bracket. Traditionally, these two fields of study have been quite separate. The exhibition establishes a connection through the use of narratives, serving as a unifying element. It is important to note that this does not encompass the entirety of the African continent, nor does it include all its regions. Undertaking such a task would undoubtedly be a colossal endeavor. However, connections are established across modern state boundaries, where colonial borders have been drawn through ethnic and/or cultural entities.

As articulated on the museum’s website, the exhibition’s objective is essentially this:

“The exhibition acknowledges the intersections between certain historical arts and oral traditions and places historical works made by artists across sub-Saharan Africa during the 13th to 20th centuries in conversation with contemporary works by African artists working around the globe.” (https://www.slam.org/exhibitions/narrative-wisdom-and-african-arts/)

The introduction to the catalog, authored by Nichole N. Bridges, the editor of the catalog and the curator of the exhibition, articulates the conceptual underpinnings of the “Narrative Wisdom” initiative.

“Narrative Wisdom and African Art considers ways in which historical and contemporary African arts make visible narratives that are rooted in an individual’s or a community’s collective memory and knowledge. The point of departure for this exploration are arts at the intersection of the visual and the verbal as well as pictorial arts that feature figurative scenes suggesting part of or an entire narrative. Although the exhibition takes a sweeping approach, incorporating arts made by artists across sub-Saharan Africa from the thirteenth century in dialogue with contemporary works by African artists working around the globe, this study does not purport to be comprehensive in its scope in terms of either geographical and cultural representation or the many nuances of narrative and its intersections with the visual arts.” (p.15)

Notably, Nichole Bridges regards the exhibition as a “study,” thereby acknowledging the fluidity of our knowledge interests and the continuous expansion of our knowledge. This study unquestionably contributes to the expansion of our knowledge. The wisdom of the narrative is synonymous with knowledge. This knowledge facilitates a more profound comprehension of the fundamental elements that comprise African art. The narratives adopt diverse approaches and perspectives, thus facilitating a multifaceted examination of the subject. From this perspective, the study does not culminate in a definitive outcome, but rather, it is an ongoing process. This dynamic process bears resemblance to the Ifa divination method, which is extensively explored in this study. The Babalawo, the diviner, initiates the process by casting the kernels or the chain, and subsequently, he methodically navigates the realm of explanatory phrases, sentences, paragraphs, and stories.

Assessing the complete scope of the exhibition (drawn from the printed document, the catalogue/book and not by experiencing the exhibit myself) we came to the conclusion that it is a selective ensemble of most of the areas of African art, that have been the object of interest, research and public presentation at least during the past 50 years or so. More or less every well known, genial and famous creative production is included:

The Chokwe chairs, masks, musical instruments, the vessel lids, the orator’s staffs, gold weights (academically “Figurative Counterweights), drums, Adinkra cloth and Asafo flags from Ghana. Dahomey scepters, Abomey bas-reliefs and textile appliques, the Bamum king list (Cameroon), the Ethiopian Queen of Sheba story-painting (“graphic novel”), commemorative cloths, graphic scripts, Yoruba Ifa-oracle implements and portals, Benin brass plaques (copper alloys).

Popular art by Tshibumba Kanda Matulu, DRC, Kwame Akoto from Ghana, souweres from Senegal with Gora Mbengue and Mor Gueye,

Modern artists Ibrahim El-Salahi, Yinka Shonibare, Sokari Douglas-Camp, Chéri Samba, Fabrice Monteiro, Julien Sinzogan. Photography by Moneta Sleet Jr., Gosette Lubondo, Fatima Tugger, Aida Muluneh, Sue Williamson, Sammy Baloji and Goncalo Mabunda.

Not each and every is known to everybody, i.e. besides the mainstream and famous, also less known, but not less impressive artists and objects are assembled.

All in all a valuable introduction of African art, modern and up to date, especially in the way the traditional and the modern are not only juxta-positioned, but connected and therefore surpass the general – false – binary attitude to create tradition versus modernity as opposites, as if the one had nothing to do with the other.

Here and there one wishes this or that piece or artist could have been included, but this is not really important, as – and the authors themselves argue – the approach is not completeness, and can not be! More important are the linkages, and they have been drawn here in an examplary mode.

Nevertheless, may be, one should mention a selection of artists not included here, because the present choice also is accidental, depending on availabilities, properties and personal preferences. My list now is also guided by whatever limited knowledge we might have, but recalls the fact, that there are many more and many very interesting artists providing a lot more narrative:

“Popular” artists:

The coffin makers of Ghana (Samuel Kane Kwei); the cement grave sculptures in Ibibio land of Eastern Nigeria (Sunday Jack Akpan); the wooden grave yard posts “aloalo” in Madagaskar; sign and portrait painters of Sierra Leone, Ghana and Nigeria (Middle Art); the wall painting women of the Ndebele in South Africa and among the Igbo in Nigeria; the “Voodoo” artist in Togo (Abagli Kossi) and in Benin; “Tingatinga” from Tanzania;

Painters:

Twins Seven Seven; Malangatana; Moke; Obiora Udechukwu;

Photographer:

Seydou Keita; J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere

Textiles:

„Kuba velvets“

Sylvia Sukop commences the chapters with a contribution on a Congolese photographer, “Gosette Lubondo and the Restless Ghosts of Time.” She employs a technique of multiple exposures, achieving effects reminiscent of the early days of photography, specifically “spirit photography.” The nature of her work is as follows:

“imaginatively animating a history that is otherwise absent from the photographic archive while infusing it with an indisputable, embodied presence.” (p. 24)

The second chapter, entitled “Ties That Bind. Blending Contemporary Art and Historical African Art” is authored by Smooth Nzewi and Emeka Ogboh. The latter is interviewed by Nzewi. The chapter’s primary focus is an in-depth exploration of Ogboh’s artistic practice, with a particular emphasis on his sound installation works. The written medium, however, proves inadequate in fully capturing the profundity and allure of Ogboh’s artistic oeuvre. Regrettably, the text reveals a persistent adherence to a colonial perspective on Africa, perpetuating antiquated and uncritical anthropological academic ideas. In these instances, one cannot help but lament the absence of a contemporary, African academic perspective that could have rectified these missteps before publishing. The text’s use of language evokes the racist discourse of South Africa’s apartheid era. Contrary to the assertions made in the text, the presence of “Bantu” groups or subgroups remains unconfirmed. The existence of a Bantu language family is acknowledged; however, the term “Bantu” is not applicable beyond this linguistic affiliation. The term “Bantu” is derived from the plural prefix “ba” and the term “ntu,” signifying “being.” The singular form for human being is “muntu.”

The continued usage of the term “thumb piano” disregards the racist connotations inherent in the term, which belittles a remarkably sophisticated and artistic musical instrument. The Shona “mbira” specifically refers to a particular instrument and cannot be used to refer to any other lamellophone. The same holds true for the “sansa.” This perpetuates the colonial perspective of Africa as a single country with a unified language. This perspective is reminiscent of the colonialist notion that all African countries are culturally homogeneous, a concept that was further popularized in South Africa under the apartheid regime, where any cultural element deemed to be “African” was oversimplified and categorized as uniformly Bantu…

Under the heading of “SonicVisions” those terms are repetetively used…

For Nzewi it would have been helpful to confront Emeka Ogboh with similar approaches with the presentation of the “Sound of Africa” – as e.g. was exemplary realized in the Geneva museum of ethnography – musée d’ethnographie de Geneve in 2009 with “L’air du temps – in tune with the times”Besides those deplorable shortcomings a lot what is articulated in the interview is very relevant and true. Most encouraging the discourse on the question of “historicizing” museum objects.

Orality

Under ”Orality and Objects. Models for Understanding” by Jacky Maniacky from the Tervuren Museum in Belgium we are surprised to read:

“In West Africa, storytellers are usually called griots…” (p.52). This is not true at all! Within the francophone West Africa it has become a kind of general designation for a storyteller or praise singer to use the term griot mainly among intellectuals and persons with an international outlook. But anybody who is a bit more familiar with different cultural regions and languages knows, that there are specific terms for this phenomenon everywhere. In Mali, Mbamana speaking areas, the term is definitely “Jali” and the female version “Jali Mussow (Muso)” in Senegal among the Wolof it is “Jewel.”

However, within the anglophone West African context, the term “Griot” is not utilized, a circumstance that is both valid and justified. This is due to the fact that praise singers and storytellers in this region possess unique characteristics that distinguish them from one another.

The “Bantu migration” is once again invoked, yet it fails to acknowledge the critical component of African languages being tonal languages, whose music and narratives are inherently intertwined.

The absent mention of tonality in languages such as Yoruba results here in a significant disregard of artistic depth, as tonality plays a crucial role in the expression of artistic complexity in these languages.

The Yoruba language tonality is given adequate attention and space in the later chapter by Yomi Ola on Yoruba sculpture and portals. (119-127)

Speaking Art

The concept of “Speaking Art” is a notable example of this phenomenon. In this context, the concept of the verbal-visual nexus in Akan and Ghanaian art studies emerges as a pivotal area of inquiry. In this work, Quarcoopome draws parallels between the renowned Akan gold weights, minute sculptures, and the proverbial fundus of the Akan language. This endeavor, while undoubtedly fruitful, is predicated on the assumption that the interpreter possesses a comprehensive understanding of the pertinent proverb. The limited access of any ordinary language user to the uncountable wealth of proverbs is a matter that merits further scrutiny. The absence of a comprehensive, systematically collected body of proverbs, representing the collective wisdom of numerous elders who are both knowledgeable in their culture and proficient in their language, suggests that we are resorting to arbitrary interpretations. While it is possible that we are fortunate enough to have found a proverb that aligns with our intended interpretation, in most cases, we are merely attempting to identify a suitable proverb.

To trace the narrative linked to a particular orator’s staff – the orator’s staffs carry small sculptures as well and in this they conform with the weights – also concerning the proverbial link. First of all the description has to be agreed upon.

To illustrate this point, consider the description of the minute sculpture, defined by the author as “The lion being patted by a boy” (p. 61, Fig. 33) This is a questionable regard. It is crucial to question the initial assumption that the figure is a boy, as opposed to an elderly individual.

“The relative sophistication (how presumptuous is that?) of the staff’s imagery lies in its moral and philosophical underpinnings; one shows a boy patting a striding lion (Fig. 33) – the youth either oblivious to the creature’s dangerous disposition or immensely stupid.” (p. 60)

The author of this chapter does not include other obvious connotations, and this is true of all the other cases as well. The reason for this is unclear. In all other instances throughout the catalog/book, the term “leadership” is employed, which, in this author’s opinion, embodies a conservative societal ideology. In this particular instance, however, the term may serve as a symbol of the depicted individual’s authority over the perilous lion, potentially signifying spiritual authority as well. It is imperative to refrain from speculating about the human depicted here, irrespective of whether it is a “boy,” “elder,” “priest,” “king,” or any other designation. A thorough examination of the sculpted neck might offer valuable insights. This analysis necessitates the expertise of an individual well-versed in the cultural context, whether it be a local knowledgeable person or a trained anthropologist. It is imperative to exercise restraint and refrain from speculating, as this practice constitutes a lack of respect for the artwork and the artist.

It is not within the scope of this review to address all possible interpretations; such an endeavor would be exceedingly extensive. However, it is imperative to interrogate each interpretation. We hereby propose a revision of the presented fiction, reinterpreting it as a work of “science fiction.”

This is particularly unfortunate because the chapter includes further interpretations of the symbolism of such profoundly rich “adinkra” cloths and “asafo” flags.

The Asafo flags are also discussed in a subsequent chapter, “Grounded Narratives,” by Elyse Dianne Schaeffer, where the following lines are presented:

“Although the specific events to which these vignettes refer have not been identified, it remains clear that the banner commemorates a significant moment in the history of the land and its residents.” (p.197)

The beautiful piece, especially presented in the book with a special pull-out page to allow its full length, is included in the exhibition, but it hasn’t been sufficiently and successfully studied. Where is the research that should have been done? Where is the narrative when narrative is the central theme?

In the section on Asafo flags in the “Speaking Art” chapter, Doran Ross and Kwame Labi are criticized for “only vaguely” alluding to, if not underscored, the intertextuality in Fante flag symbolism” (p.65), but no evidence is provided. At the same time, the author describes the figures on a flag (fig. 39), among other things: “the flags center shows a Black person carrying on his head an orb or globe…” (p.65). People are shown in different colors, for different meanings, nothing to do with “black”, some are white, pink or black. The color symbolism should have been revealed to the reader.

I am not sure against whom the author’s warning at the end of his text is directed:

“Ongoing reliance on Akan philosophy and oral literature as a framework for interpreting non- Akan manifestations of the verbal-visual nexus persists, perpetuating the notion of the Akan’s sole ownership of this knowledge system.” (p.73)

It seems more than obvious that the author is right to question the criticized approach.

No one would use, say, French philosophy to explain German literature.

Why is Kente cloth not even mentioned? It would have been relevant, especially since it is industrially copied on ordinary textile color prints to be used as a “wrapper” or “lappa” or, as it is called in much of francophone West Africa, as a “pagne”. The use of traditional textile, i.e. handwoven cloth design as a pattern for industrial production in general is relatively recent. However, I encountered the use of the Kente pattern as early as 1964 in Cotonou, then Dahomey, now Benin. Since there are many variations of a Kente cloth, it would have been particularly interesting to know which design became the pattern for mass production and how the mass production of a very individual pattern was received by the customers.

Did the design of the Kente cloth in question address a family? A position? A town?

Problematic Leaders

The next major section is headed by the aforementioned term “leaders” – a term that tries to escape the traditional designations of “chiefs,” “kings,” “emperors,” “dictators,” etc., but has another connotation that comes from a conventional, “non-critical,” conservative sociological theory of society. A “leader” stands for a hierarchical concept that does not take sides with the people, in this theory there are so-called “legitimate” leaders. The term “leader” sounds as if it is a natural gift that allows a person to be a leader, instead of realizing that behind the neutral term “leader” there is a striving for power. Who is a legitimate leader, who is usurping power?

Whatever “leader” is, it is at least an unfortunate term with a questionable concept behind it.

The term “leader”, at least in Europe, has become problematic, has definite negative connotations, because during the fascist period in Germany we had Hitler, the “Führer”, i.e. “leader”, and in Italy we had Mussolini as the “Duce”, i.e. “leader” as well.

In the African context, where traditionally there have been all sorts of models of how to live together as human beings, the greater part of societies have organized themselves into political systems, with various arrangements around a power, an individual, or a family, or an age, and often with balancing agencies. “Leaders” is misleading to me here. I would have preferred the term “politics” or “power.”

Nichole N. Bridges is responsible for this important piece in this admirable product of a book.

Her chapter is entitled “The Party Line and the People’s Parables. Leadership Arts Shaping Narrative.” (76-117) At the beginning of this “essay,” as she calls it, Nichole Bridges emphasizes that:

“Since oral histories and oral traditions have bolstered the historical and genealogical origins of leaders, chiefs, and kings in many African societies, leadership arts – arts created to extol these rulers’ authority – are a wellspring for intersections between oral traditions and the visual arts. Functioning to reinforce a leader’s authority, the overarching narrative of these arts vitally supersedes any sequential one. Examining the perspectives not only of the leader – the instigator of leadership arts – but also of a leader’s constituents, this essay positions figural and pictorial leadership arts as inherent anchors for narratives that affirm a ruler’s legitimacy and reach.” (77)

She begins with an analysis of the Angolan Chokwe chief’s chair. This is obviously not just a piece of furniture, but a symbol and expression of the power of its owner, “the patron who commissioned it” (85). The origin of the chair as such is given:

“Inspired by European high-backed chairs imported as trade goods in the region since the seventeenth century, Chokwe chief chairs reflect their patrons’ and makers’ ingenuity in transforming a utilitarian foreign form into a symbolic prestige object with deep local significance.” (85)

I would have liked to see this approach to imported objects or images applied throughout the catalog.

Nichole N. Bridges has juxtaposed the sculpture “The Throne of Beyond” by the Mozambican artist Goncalo Mabunda (b. 1975) from the year 2019 and justified it with the remark:

“Echoing the silhouette and ornamentation of the historical Chokwe chief’s chairs from Angola – also a former Portuguese colony that endured its own prolonged civil war (1975-2002) – Throne of Beyond symbolizes a collective seat of empowerment, commanding society to transform the devastation of war into generative possibilities.” (p. 83)

Why not just declare it a strong anti-war object? It is an open attack on the war-mongering political leaders who base their power on the use of all kinds of lethal weapons.

In addition, the Angola war was first of all – in German – a so-called “Stellvertreterkrieg” – proxy war – during the Cold War – between East and West. It would have been the appropriate place to delve deeper into post-colonial violence sponsored by outside powers. In the Angolan civil war, the United States supplied arms to the FNLA (Frente Nacional de Libertacao de Angola) and UNITA (Uniao Nacional para a Independencia total de Angola) against the MPLA (Movimento Popular de Libertacao de Angola), which formed the central government after independence from Portugal and was supported by the Soviet Union and, among others, the Democratic Republic of Germany (GDR) and Cuba.

The connection with Angola and the Chokwe chiefs seems obvious, but could be explained beyond the fact that both countries were former Portuguese colonies.

What is the reason for omitting U.S. involvement here?

The Leader chapter continues with “The Party Line 1: Courtly Commissions.” The exhibition includes regalia from Dahomey (Benin) and Bamum (Cameroon) kingdoms: Royal scepters from Abomey and a “King List Drawing” from Bamum. The exhibits are described and their context, their functions presented. The objects range from traditional handycraft to “modern” inventions, like the Bamum “King List” by Ibrahim Njoya from around 1930. (p. 88)

Nichole Bridges quotes art historian Annette Schemmel:

“…the king lists and other Bamum drawings were important ‘pictorial tool(s) to affirm dynastic lineage and implement an official Bamum history at a moment of confrontation with the European intruders as well as internal power struggles.’ “ (p. 94)

The famous Benin lost wax copper alloy plaques from the Benin Palace in Nigeria are mentioned. Curiously, the “British raid and looting of the palace in 1897” is mentioned, but not the reason for the colonial “punitive” action. This is half the truth.

The British tried to visit the Oba of Benin despite a warning that he wouldn’t be available because of religious celebrations. The British ignored the warning and were forcibly prevented from entering the Benin kingdom and killed.

6 British officers and their 200 African porters were ambushed and killed.

A “punitive” action by the British followed, with 1,200 soldiers destroying the palace and the city. The king was banished to Calabar in the east of the later colony of Nigeria. The looting of the plaques from the palace meant that they were distributed all over the world, demonstrating the high level of artistic ability of Benin artisans. Almost all ethnological museums in Europe and the United States boasted of their possession. Today they are in the international headlines with the demand for their restitution.

The next section is entitled “The Party Line II: Popular Productions”

“The Queen of Sheba” Graphic Novel

The “leader” remains the emphasis also in this section, beginning with the famous picture story – frame by frame – of the Queen of Sheba’s trip to Jerusalem. Not finally clear, when the story became a genre painting, the main push forward it’s popularity was the coronation of Haile Selassie I in 1930. Followed by the increasing international interest in the country and then the Italian war against Ethiopia, 1935/36 and the ongoing occupation until the liberation in 1941.

Again the liberation with the comeback of the Emperor promoted the visualized legitimation of the rule of the Ethiopian emperor.

The pull-out illustration on p.90 shows one version of the painting of “The Queen of Sheba’s Visit to King Solomon”. For quite some time there was no proper designation for the kind of art taking up secular motifs (motives) in the style of the traditional paintings of the Ethiopian ‘coptic’ churches. Thanks to the research of the late German anthropologist Jörg Weinerth (1960 – 2023) nowadays we prefer his proposal for the term “antika”-painting. (Weinerth 2014)

Unluckily we are not told who the painter was and what the writing on the canvas tells us. This contradicts the intention of the exhibition project as a whole. There, where an authentic statement by the painter him/her self is provided, it has not adequately been appreciated. It is not comprehensible why? The Amharic script can be deciphered and translated. We have over a Million Ethiopians living in the US as they are refugees of the violent communist “Derg”- Regime.

The pull-out reproduction, prominently placed, should have received more attention. On the right side of the painting a long text is included. As the quick glance of an Amharic speaker reveals, it is the standard story of the Queen of Sheba’s trip and the story preceding it. It would have been great to read the Amharic text in translation! From an academic point of view a transliteration would help in appreciating the language sound – and would open up the hidden words to an interested readership, allow transparency and end cultural isolation.

Of particular interest is the date given on the canvas, 1936 Ethiopian calender, i.e. September 1943 – to August 1944, Gregorian calender! Painted after the end of the Italian occupation in 1941, during the second world war. The Emperor Haile Selassie had returned from his exile in Britain with the help of the British forces. The Americans helped to convince the British, who had intended to stay, to leave the country. The period under the Italians had pushed the market for the “antika” paintings.

History is not really told properly by writing:

“Across the continent in Ethiopia, fresh from the 1896 Battle of Adwa, which successfully thwarted the first Italian attempt to colonize the region, Emperor Menelik II (r. 1880-1909) employed a longtime local narrative.” (p. 94)

In fact, Italy had already taken over the north of the Horn of Africa, today’s Eritrea, as a colony in 1890. The Battle of Adwa stopped the Italian attempt to conquer the Abyssinian Empire. The Italian fascists under Mussolini avenged the defeat with their gas war from 1935 to 1936 and were driven out by joint British and Abyssinian troops in 1941.

Somalia also became an Italian colony in 1908!

The Saint Louis Art Museum and the German publisher Hirmer are indeed pioneers. It is not so long ago that general art museums did not consider African art as a genre to be exhibited, and at the same time anthropological museums did not want to expand their scope to include contemporary African art.

The celebration of murderers

The chapter continues with the photographic celebration of “leaders” – again, in most cases, according to world standards – not famous liberators, but rather belonging to the group of the harmful, murderers or assassins – with a few exceptions, often unjustifiably glorified. Fortunately, the connection with modern art opens up a critical perspective. Fabrice Monteiro’s installations question the dictators’ culture of self-praise.

The commemorative cloths are included in this critique of the glorification of leaders. What is not mentioned here in full is the function of many of the printed cloths. The dictators or party politicians use the textile prints for their (pseudo) election campaigns or other celebrations – a useful instrument in societies with low or no literacy. Distributed for free or sold at low prices, political prints were soon despised and worn only by the poor. At the same time, it became dangerous to wear the deposed leader’s head in the face of the new autocrat. This is part of the story!

Nichole N. Bridges chose the lives of two leaders to show how they became influential and important figures with the support of popular art. She chose Patrice Lumumba (1925-1961) of the Congo and Amadou Bamba (1853-1927) of Senegal.

The artist Tshibumba Kanda Matulu (1947-1981) created a pictorial history of the Congo in which Patrice Lumumba plays an important role, his rise from a lowly state official to prime minister. The style he uses he shares with the popular genre sign painters. Paintings the people loved to put up in their parlours.

Part of the story is the involvement of the anthropologist Johannes Fabian (1937-) and his then wife Szombati-Fabian in the realization of this project. Why this part is left out is astonishing or disturbing. In the beginning the couple anthropologists have collaborated in this project. Later they separated and it became an issue of quarrel and resulted in the usual gender fate: The male partner published in 1996 further research on his own: Fabian/Matulu 1996.

Concerning Patrice Lumumba, over the years, there have been doubts that his assassination was the work of the CIA and the Belgian secret service, but in the end it was confirmed. Lumumba was assassinated just in time for the new U.S. president, Robert F. Kennedy, to take power. It was not just a “Western coup” – it was an anti-communist assassination during the “Cold War” to prevent a socialist politician from coming to power in Africa. The Congo – including mineral-rich Katanga – was to remain in the U.S.- controlled capitalist world. His body was dissolved in a barrel of acid liquid. The story also goes that years later, one of the Belgian police officers involved, who had kept a tooth of Lumumba that had haunted him, took it and threw it into the North Sea. All this was reported by the fortnightly political news magazine Jeune Afrique from Paris.

The Senegalese personality chosen by Nichol N. Bridges is the founder of the Islamic Brotherhood of the Mourides, Sheik Amadou Bamba. The French colonial administration exiled him to Gabon in Central Africa because he was an outspoken anti-colonialist.

On the boat to exile, where he was forbidden to pray, he is said to have taken his prayer mat out to sea and prayed. This scene became a favorite motif for painters on reverse glass – souwere – such as Gora Mbengue (1931-1988) and Mor Gueye (1926-).

I have used the term “popular art” as it was common in the 1960s as a very positive designation. Ulli Beier (1922-2011) is largely credited with “discovering” it as a unique modern African art format. When I met Okwui Enwezor (1963-2019), Nigerian global curator, at the opening of the Tate exhibition “Century City: Art and Culture in the Modern Metropolis” (2001) in London, where he had curated the “Lagos 1955-1970” section and I had prepared the “tape” for the sound installation that provided the permanent sonic Lagosian feeling of the 50s and 60s, he made me aware of the problematic use of the terms “popular culture” and “popular art”.

Now, while working on this review, I came across the definition, the argument, that Enwezor was talking about in printed form in his 2009 book “Contemporary African Art since 1980” in the section “Compilation” on p. 340. Since he is no longer with us and will not be promoting his position, I want to quote it in full here, as I think it is an important clarification of the use of the term:

“Popular Art

The category of Popular, or Urban, Art has been used to describe the work of artists living mostly in urban centers who were not formally trained in Western-style art. And whose oeuvre often includes signage and narrative painting made for local clients. In spite of its local focus, however, the initial popularization of such work in the contemporary art world depended on the support of expatriate clients and critics. Two models proposed by Johannes Fabian and Karin Barber have dominated intellectual debate on the meaning and scope of popular art in postcolonial African cultures. While Fabian sees popular art as a site of contestation of power in colonial and postcolonial society, for Barber it is defined not so much by its relationship to the politics of power as it is by its ability to encompass the arts and by its “infinite elasticity.” In both models, popular art is seen as the constellation of visual practices operating outside the canon of equally intractable “traditional” and “elite” art. Nevertheless – as has been made amply obvious, especially with recent scholarship on visual culture, but also in art history and anthropology – popular art as a definite aesthetic and conceptual category is untenable. Its continued currency in the field of African art points to the lingering influence of critical paradigms that have done little to acknowledge the complex, often intractable, and therefore undefinable realities of postcolonial Africa on the one hand, and contemporary art and cultural practices on the other.”

Coming back to the chapter by Nichole N. Bridges.

I take this review of the Saint Louis Museum exhibition catalog/book as an opportunity to look back at the history of the exhibition of African art after World War II, focusing on exhibitions from 1962 onward, mainly in Europe and Germany. At the same time, it is a very personal account, as I myself have become an agent in this field, from observer to researcher, collector, writer, and curator. Of course, my account is by no means objective or complete, it is accidental, it is very subjective, depending on where I went and encountered African art and African art exhibitions.

Excursus

Exhibiting African art has long excluded modern art production in Africa. It was one of the achievements of Ulli Beier (1922-2011), who worked in Nigeria after World War II, initially as an extramural studies staff at the University College of Ibadan, to give contemporary African art a public space at home – in this case in Nigeria – and to slowly open up modern African art to the world outside Africa. The journal Black Orpheus, No. 1, September 1957, (initially edited by Ulli Beier and Janheinz Jahn (1918-1973), later by Ezekiel Mphahlele (1919-2008), Wole Soyinka (1934-) and Ulli Beier, and later again with changing editors) published the first articles on artists such as Ibrahim el Salahi (1930-) from Sudan (included with several works in the Saint Louis catalog), and Malangatana (1936-2011) from Mozambique, both No. 10, 1961/62, and presented Oshogbo artists from Nigeria, No. 12, n.d., probably 1963.

Ulli Beier was also responsible for the first exhibition project that questioned the generally accepted “anonymity” of African sculpture. It had become something of a trademark, “anonymous” standing for the fictitious African “tribal” society that did not know that the originators of its art were in fact individuals. “Anonymity” had become a kind of mystification of the supposed collective effort against modern individualism.

In most cases, collectors simply did not want to know about potential identifiable artists. An individual sculptor wouldn’t have fit into their preconceived notions of “primitive” people anyway. If they had seriously inquired about the artists, they would have found out. The lack of vice/verse language skills wouldn’t have been the problem. The attribution to an individual creative force was out of the question. “Primitive carvers” were supposed to be only outlets of a collective – more “instinctive” – source. The myth of the “anonymous” was even present in Susan Vogel’s 1991 “Africa Explores” catalog!

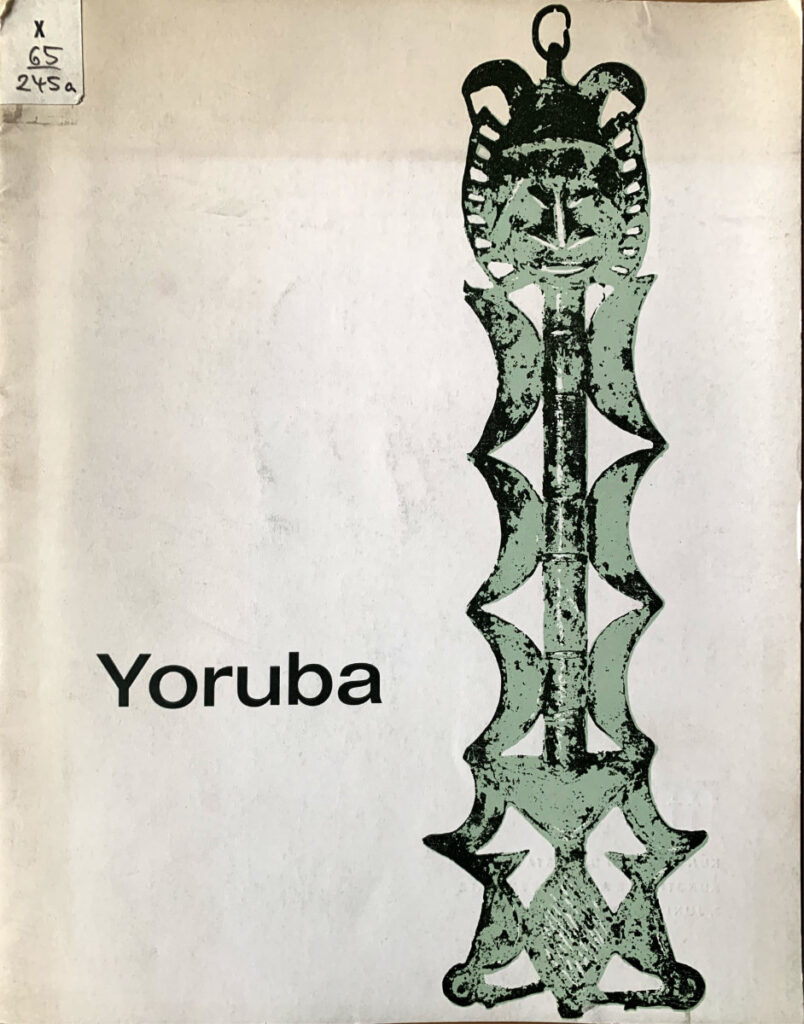

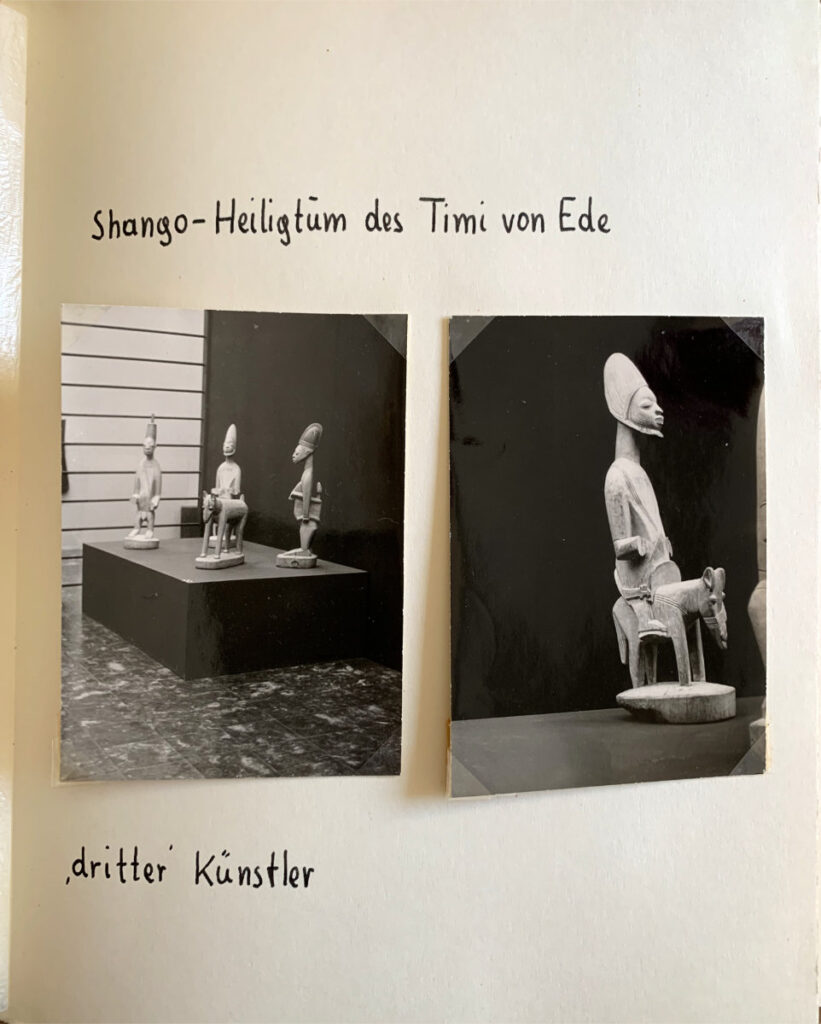

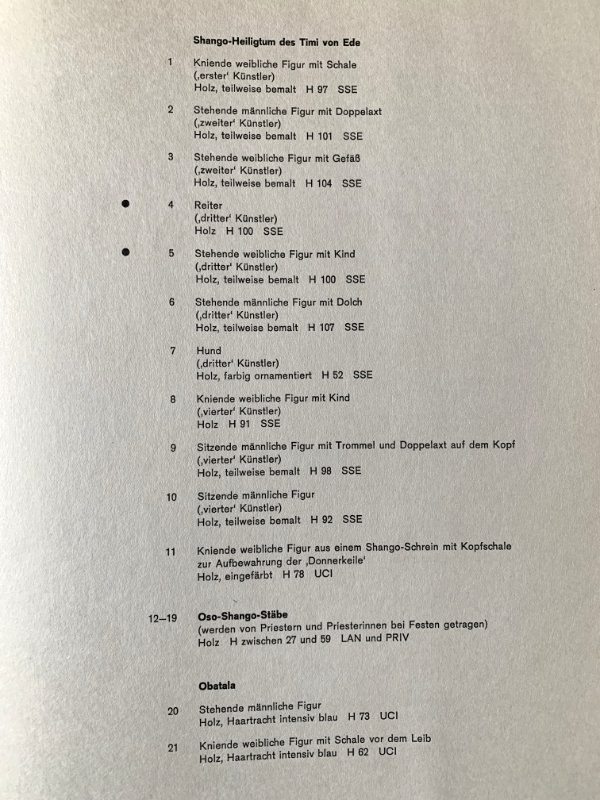

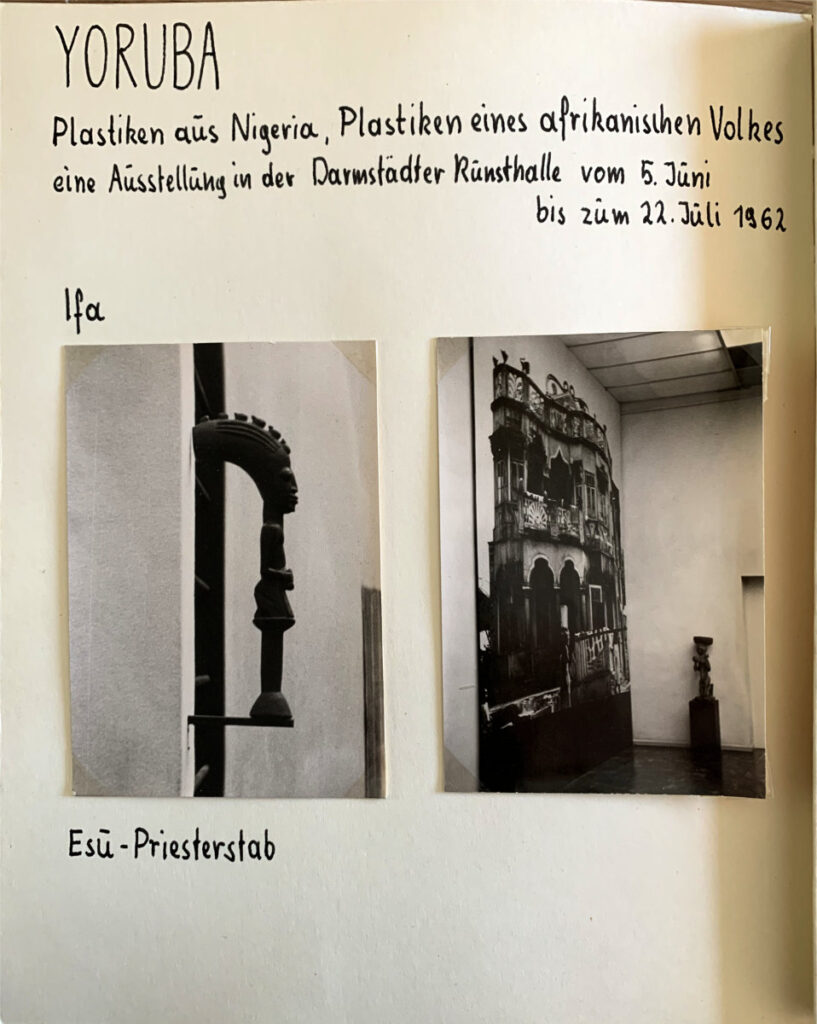

In the early 1960s, Ulli Beier, together with Janheinz Jahn, was responsible for a new approach to the appreciation of the individual artist in the traditional context. They undertook the experiment of analyzing the sculptures of a particular Yoruba shrine, that of the Timi of Ede, in western Nigeria. Ede is a town not far from the city of Oshogbo. According to a number of criteria, they were able to attribute the works to four artists, thus establishing a single artist one by one. The result of this research was presented at the Kunsthalle Darmstadt (Hesse, West Germany) by the Kunstverein Darmstadt in 1962 (June 3 to July 22). As far as I know, it was the first time that traditional sculptures attributed to specific artists were presented.

The title of the exhibition was “YORUBA. Plastiken eines afrikanischen Volkes“ (Yoruba Sculptures of an African people.) The catalog text was written by Ulli Beier.

(photographs I took of that exhibition)

This particular aspect reminds me of the general ignorance on the part of Anglo-American academia with regard to non-English research publications and exhibitions. This even applies to current Anglophone curators, for example, even in Berlin, Germany. Working in a German urban environment, they might as well ignore literature written and published in German. One might have expected that the World Wide Web would help to reduce these parochial perspectives, but this is not the case at all.

A commendable exception in the present publication is the contributions by Elyse Dianne Schaeffer, who shows a broad horizon in her research, including European, German studies.

Slowly, anthropological museums, especially those with a focus on African cultures, began to create spaces for contemporary African art. There were even museums that completely changed their acquisition policy, such as the Völkerkunde Museum in Frankfurt am Main, West Germany, under the directorship (1985-1989) of Prof. Josef Franz Thiel (1932-2024), a former Steyler missionary (SVD – societas verbi divini). He conceived a new basic concept: to build up a collection of contemporary African art around 1985.

Dr. Johanna Agthe

He selected individuals whom he considered competent to go to a particular region in Africa and purchase a considerable number of works of art that resembled the modern art production then underway. Among his own staff, he was privileged to have a curator for Africa who had East Africa as her domain. Dr. Johanna Agthe (1941-2005) had already established her own contacts during her visits to East Africa, especially Nairobi, from where she was able to intensify her research and acquire a representative collection. Among the artists she knew was the Ugandan Jak Katarikawe (1940-2018), whom she presented in several small exhibitions.

At that time, several collections of so-called “Square Paintings” or with the original artist’s name “TingaTinga” from Tanzania/Mozambique were offered by galleries in Frankfurt am Main. And it was no coincidence, as I was to observe, that the anthropologist curator of the Museum of Ethnology chose themes such as “magic”, as opposed to “the railroad” or “the ocean steamer”, which would have been equally suitable… (W. Bender 1989: “Moderne Kunst in die Völkerkundemuseen!/Modern Art to the Ethnographic Museums!” in: Elisabeth Biasio: Die verborgene Wirklichkeit. Drei äthiopische Maler der Gegenwart/The Hidden Reality. Three Contemporary Ethiopian Painters, pp. 182-196, 203-206, 210.)

In her review of the Frankfurter Völkerkundemuseum and the new collection strategy, the new – and present – Africa curator, Julia Friedel, comments:

“Regionale Schwerpunkte der Sammlung liegen bei Kunst aus Nigeria, Senegal, Südafrika und Uganda. Denn neben Johanna Agthe erwarben auch andere Persönlichkeiten Werke für das Museum, die sich aus eigenem Interesse heraus intensiv mit Gegenwartskunst aus Afrika beschäftigten. Thiel beauftragte diese museumsexternen Personen Mitte der 1980er-Jahre, Ankäufe für die Afrikaabteilung zu tätigen. So ist die Sammlung, wie wir sie heute vorfinden, eng verbunden mit den heterogenen Geschichten ihrer Entstehung und den Biografien der unterschiedlichen Sammler. Sie dokumentiert nicht nur das Kunstschaffen in ausgewählten Regionen Afrikas zu einer bestimmten Zeit, sondern spiegelt auch das individuelle Interesse der jeweiligen Persönlichkeiten wider und gewährt einen Einblick in deren Herangehensweisen.

Regional emphasis lies on the art from Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa and Uganda. Because besides Johanna Agthe also other personalities, which out of their own interest had engaged themselves with contemporary art from Africa, acquired works for the museum. Thiel asked these external persons in the mid-eighties to acquire works for the Africa department of the museum. That’s why the collection, as we find it today, is closely linked with the heterogeneous stories of its formation and the biographies of the diverse collectors. It does not only document the art production in selected regions in Africa, but mirrors the individual interest of the particular personalities and allows an insight into their kind of approach.” (Friedel 2018:22; my translation)

Part of the new collection policy was the publication of catalogues. The one on East Africa:

Agthe, Johanna 1990. Wegzeichen – Signs. Kunst aus Ostafrika 1974-1989/ Art from East Africa 1974-1989. Sammlung 5: Afrika. Frankfurt am Main (Museum für Völkerkunde)

Hans Blum

In the case of South Africa, a personality was chosen from Prof. Thiel’s personal circle, the Protestant Dekan Hans Blum, who was responsible for the museum prints created in missionary institutions. We have to keep in mind that this was the time of apartheid and sanctions, an internationally agreed ban on cultural cooperation with official South African institutions. But we have to remember that there were many artists in South Africa who were excluded. And there were exiles in Britain and elsewhere who were producing anti-apartheid art, see for example Resistance Art (Williamson 1989).

The publication dealing with the acquired prints:

Stötzel, Monika 1987. Botschaften aus Südafrika. Kunst und künstlerische Produktion schwarzer Künstler. Roter Faden zur Ausstellung 11. Frankfurt am Main (Museum für Völkerkunde).

In her review of the acquisition history of the ethnographic museum in Frankfurt am Main, Friedel explains the procedure of pastor Blum:

„1964 ging der Pfarrer Hans Blum als Missionar mit seiner Familie nach Südafrika; seine Station lag unweit des Kunstzentrums Rorke’s Drift Art and Craft Centre in der Provinz KwaZulu-Natal. Er begann, privat zu sammeln und Ausstellungen in Deutschland zu organisieren, zum Beispiel »Passion in Südafrika« von 1981. Blum interessierte sich vor allem für die Darstellung der Lebenssituation schwarzer Südafrikaner sowie für christliche Motive. Mit seinen Ausstellungen wollte er nicht zuletzt auch über das Apartheidregime in Südafrika aufklären: »Ich wollte Kunst von schwarzen Künstlern kaufen, weil sie im südafrikanischen System keine Chance hatten.« (Blum 2015:280) Von Thiel beauftragt, reiste er 1986 mit einem Ankaufsbudget von 100.000 DM nach Südafrika und erwarb ausschließlich Kunst schwarzer Südafrikaner – insgesamt 600 Werke in sechs Wochen. Es handelt sich dabei vor allem um Drucke, die in den 1960er- bis 1980er-Jahren entstanden sind. Blum war es wichtig, einen fairen Preis für die Werke zu zahlen, die für die Künstler zu dieser Zeit in Südafrika schlecht verkäuflich waren. Er erwarb unter anderem Collagen von Sam Nhlengethwa, die alltägliche Szenen in den Townships zeigen, sowie zahlreiche Linoldrucke von John Muafangejo, in denen der Künstler geschichtliche und autobiografische Ereignisse detailliert verarbeitet. … 1987 wurden Blums Ankäufe schließlich unter dem Titel »Botschaften aus Südafrika« in Frankfurt präsentiert; später tourte diese Ausstellung bis 1990 unter anderem nach Berlin, Salzburg und Havanna –

1964 pastor Blum went as a missionary with his family to South Africa; his station was not far from the art centre Rorke’s Drift Art and Craft Centre in the province of KwaZulu-Natal. Privately he began to collect and to organize exhibitions in Germany (then West Germany, W.B.), e.g. ‘Passion in South Africa” in 1981. Blum was interested mainly in the live-situations of black South Africans as well as in Christian topics. With his exhibitions he wanted not in the least to inform on the regime of Apartheid in South Africa: “I wanted to acquire art from black artists, because they had no chance within the South African system.” (Blum 2015:280) Authorized by Thiel he travelled in 1986 with an acquisition budget of 100,000 DM to South Africa and bought exclusively art from black South Africans – in all 600 pieces in six weeks. Mainly prints that originated in the years from 1960 to 1980. It was important for Blum to pay a fair price for the artworks, that were not easy to sell in the then South Africa. Among others he acquired collages from Sam Nhlengethwa, that were showing daily scenes in the townships, as well as lino prints from John Muafangejo, containing historical and autobiographical events in great detail. … 1987 the acquisitions of Blum were finally presented in Frankfurt under the title ‘Messages from South Africa’; later this exhibition went on tour until 1990, among others to Berlin, Salzburg and Havanna.” (Friedel 2018:22, my translation). (Julia Friedel quotes „Blum 2015,“ the source: Badsha, Farzanah 2015. „Hans Blum im Gespräch mit Badsha Farazanah“ in: Mutumba, Yvette und Gabi Ngcobo (Hrsg.): A Labour of Love. Bielefeld (Kerber Verlag).

Thirty years later the change in the acqusition policy initiated by the director J.F.Thiel received an altogether new recognition by the exhibition and catalog by two curators, Dr. Yvette Matumba and Gabi Ngcobo from Johannesburg. They had a new regard at the collection and the collector, including a very personal approach, including the complete transparency of the exercise. (Matumba/Ngcobo 2016)

Dr. Ronald Ruprecht

For the anglophone West Africa, the director asked a former director of the Goethe Institute (the German – then still “West”- German cultural institute) in Lagos, Nigeria, to go on a shopping trip.

Dr. Ronald Ruprecht had just become interim director of the Iwalewa House in Bayreuth (West Germany, Bavaria), the Africa Center of the University of Bayreuth, founded in 1981 by Ulli Beier with my assistance. Iwalewa was then dedicated to “Art from Africa and the Third World”, and since Ulli Beier had left Bayreuth under protest in 1984, Dr. Ronald Ruprecht was chosen to bridge the absence (before his return). As the director of an institution dedicated to the promotion and presentation of modern African art, and having been to Nigeria, he seemed an obvious choice to Prof. Thiel. Dr. Ruprecht himself was puzzled by this questionable honor. He immediately told me, laughing: “I am not a specialist in African art.” His collection was considered questionable. The result of these shopping tours can be seen in the reserves of the Frankfurt museum, with the now politically correct title.

Just to give you one particular detail: Iwalewa’s collection, i.e. the former private collection of Ulli Beier, which was acquired by the Bavarian State in 1980 for the University of Bayreuth, contains the famous painting of Middle Art (Augustin Okoye, 1936) entitled: The Story of Chukwuma and Rose, oil on plywood (106 x 70,5). (Ulli Beier 1980. New Art in Africa. Berlin (Dietrich Reimer):77; Berliner Festspiele 1979:109)

A stunning example of the narrative character and beauty of Nigerian – in this case Igbo – folk art. Dr. Ronald Ruprecht bought from Middle Art a poor quality version (or inferior copy, if you will) of this his own painting – apparently Dr. Ruprecht was not familiar with the Beier Collection, of which he was then the director… Not surprisingly, these acquisitions by Ronald Ruprecht were not valued enough to be presented in a special catalogue of the museum.

But Ruprecht published a booklet entitled “Kunstreise nach Afrika. Tradition und Moderne” – “Art Journey to Africa” in 1988, collecting contributions by Josef Franz Thiel, Ulli Beier, Friedrich Axt, Gunter Péus, Walter Raunig, Winfried Schmidt, Helke Kammerer-Grothaus and himself. Even without the collected articles, the book provides a selective bibliography on “Art in Nigeria since 1950” of unique value!

Dr. Friedrich Axt

For Senegal, Prof. Thiel had chosen a private art lover, collector and patron, Dr. Friedrich Axt, a linguist from Darmstadt (Hesse, West Germany), who provided the Frankfurt museum with a representative, high-quality selection of modern art from Senegal at that time. (Catalog: Axt/Sy 1989)

Earlier I had considered it important to support the presentation of modern African art in ethnological museums. (see: W.Bender 1989: “Moderne Kunst in die Völkerkundemuseen! Modern Art in the ethnological museums!”)

After this experience, I rather departed from this strategy and opted for general art museums to take care of modern art from Africa.

After the Second World War, we can identify the following modes of presenting African traditional arts in European museums:

The classical anthropological museums present traditional sculptures in glass cases, static and with brief information about “tribe” and possibly “function”. These data were taken from the filing cabinet – often nothing more was known, except perhaps the date of acquisition, sometimes the collector! More knowledge could be found in published books or special museum catalogs.

I remember my surprise when I visited the small ethnological museum in Freiburg im Breisgau, West Germany, in 1986. There, in a glass display case, was an “African” blowing horn labeled “signal trumpet” – as if a trumpet is only to be imagined as a military support. A typical remnant of the limited, militaristic apprehension of early colonial collectors.

By the mid-1960s, the presentation had changed and the artifacts were recognized as formerly lively, mobile works of art. The best documented example of this is the then “reformed” exhibition at the Tervuren Museum outside Brussels in Belgium, then the “Royal Museum for the Congo”, now the “Africa Museum”.

When I visited in 1965, I was impressed by a dance mask that sat sideways on a platform, as if the wearer was “underneath” it.

Then, in the belated aftermath of the “primitivism” hype of the early 20th century, a new ideology emerged: African sculpture became highly valued for its aesthetics, its authenticity, its originality, and it didn’t need any commentary – it was supposed to be just art and as such self-explanatory. It was considered to have the same value as art anywhere else. There is a kind of egalitarian approach. While we are not usually confronted with much background information in art museums, in the case of traditional African art, contextualization seemed appropriate and necessary. Especially in the case of objects that were designed to fulfill a specific function within a festival, ritual, or spiritual event.

The collections of Barbier-Mueller from Geneva, Switzerland, for example, traveled through Europe in the 1980s under this “leitmotif” of the self-explanatory, self-explaining work of art. The art historian Werner Schmalenbach (1920-2010) can be taken as an example for this position, e.g. his exhibition at the “Haus der Kunst” in Munich.

His starting point was that art is universal and we can appreciate any art of quality.

Therefore, African art does not need to be explained by any curator’s comments. This would only detract unnecessarily from our judgment. The assessment that one needs contextualization to understand African art, he felt, was a paternalistic attitude and he wanted to protect the “purity” of African art from this kind of interpretive guidelines. This approach is laudable. It places African art on an equal footing with any other art anywhere.

Going to an exhibition with this basic curatorial practice meant that you really focused on the beauty of the sculpture above all else. It didn’t really matter where it came from, what society it was made in or for, what its function was, and so on.

In a way, it was a kind of liberating process of valuing traditional African art.

The incomplete object

It took a long time for ethnological art research to come to the realization that many of the sculptures in museum collections, especially masks, lacked a very important part of their original presence: the raffia or cloth headgear that covered the body. The textile mise en scène, the outfit for the production. I wouldn’t blame the collectors for collecting, but for what they didn’t collect in the first place. They left half of the artistic whole in place, a part as important as the wooden object, because they may not have understood the aesthetics, the spiritual connections. Perhaps it did not seem important enough, or simply too inconvenient, to the collectors, ignorant as they may have been.

If we take this example further, we could argue that in the context of modern art, why do collectors not take half of an installation instead of the whole creation? There is respect for the art product and the artist – these aspects were sadly lacking in the basic orientation of the African art collector.

The “Völkerkundemuseen” – ethnological museums – changed their names in order to distance themselves from their former connection with “Völkerkunde” – ethnology. The Frankfurt museum became the Museum of World Cultures, the Vienna museum the World Museum, and the Munich museum the Five Continents. The change of name was only a formal act. They continued to operate as before. The “Übersee-Museum” in Bremen, in the north of West Germany, was one of the first to draw consequences from the recognition of its colonial past and founding history. Its director, Dr. Herbert Ganslmayr (1937-1991), who together with Gert von Paczensky in the 1970s (!) wrote the first book on restitution, “Nofretete will nach Hause”(Nofretete wants to get home), reconstructed department after department in his building. The former colonial racist exhibits and commentaries were replaced by appropriate modern structures and commentaries, including social, political and environmental issues.

Similar progress has been made, for example, in the changes at the “Tropen Museum” in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, etc.

It took a long time for modern African art to reach larger and more prestigious European exhibitions.

It was finally presented on a larger scale in 1979 at the 1st Festival of World Cultures “Horizons ’79” in Berlin, West Germany. (Catalogue “Modern Art from Africa”, Berliner Festspiele GmbH) This exhibition was very influential in terms of the increasing popularity of modern African art in Europe. In addition to other German cities, it toured Amsterdam (Netherlands), Stockholm (Sweden), and London (Great Britain). (Bender 1993: 203-205)

Sidney Littlefield Kasfir in her “Contemporary African Art” (1999), of which I refer to the French translation “L’Art contemporain africain” (2000), mentions this exhibition and confuses it with the Peus Collection as such.(Kasfir 2000:135) Paintings from the Peus Collection were part of the “Moderne Kunst aus Afrika” in the exhibition “Horizonte 79”, but not only. (Bender 1993: 203-205)

Ten years later, in France the impressive exhibition “Les magiciens de la terre” in the Centre Pompidou and in La Villette, both in Paris, organized by Jean-Hubert Martin, in 1989 in the context of the bicentennial celebrations in memory of the French Revolution of 1789, marks a new step forward.

The private collection of Pigozzi, called “The Jean Pigozzi African Art Collection”, promoted modern African art with exhibitions in many cities (among others it was the exhibition “Africa Hoy” in the 1990s including the catalogues) and was followed by the “biannual” exhibition culture that developed. Since then, we have a specific feature of “biannual art”, i.e. artists who work for these events and not so much for a local or even international art public. The biennials of Dakar, Senegal; Sao Paulo, Brazil; Gwangju, South Korea.

Okwui Enwezor followed with his exhibition and book on The Short Century, the period during and after independence. It dealt with history and politics and was multi-media.

André Magnin and Soulillou 1996: Contemporary African Art. London and New York is one of the new “biannual” exhibitions.

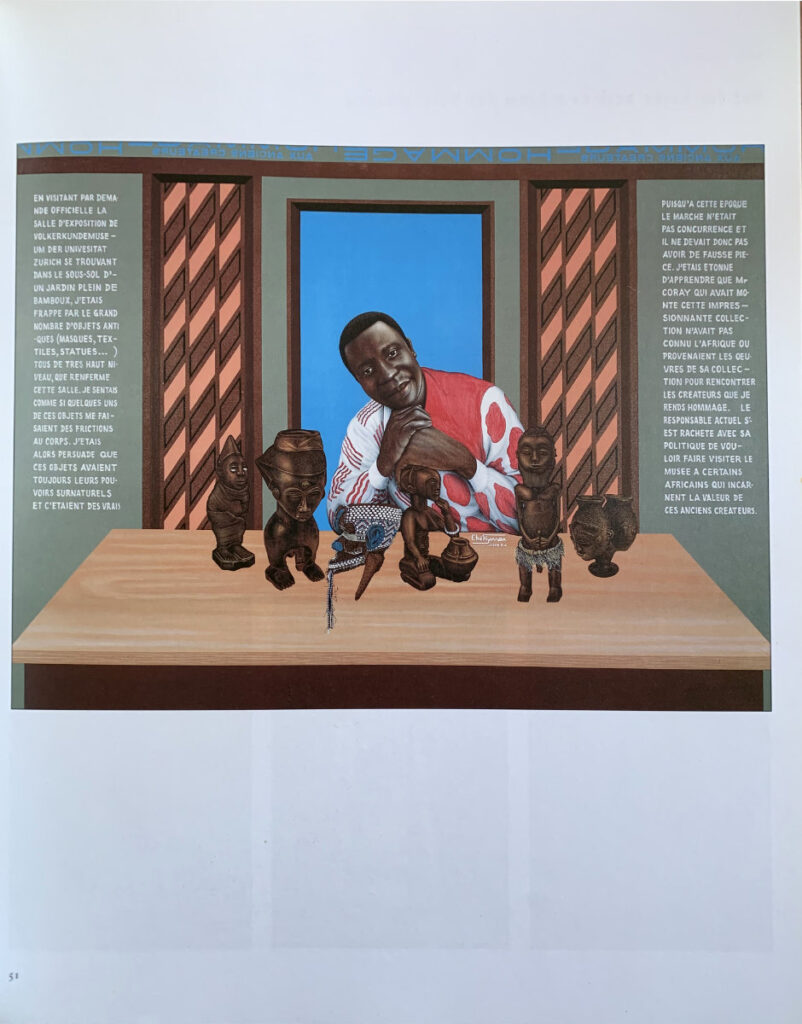

Chéri Samba

Chéri Samba (1956-) was one of the first artists to make the transition from local and tourist artist to biennial participant, and he is also represented in the Saint Louis Narrative exhibition.

He worked for years in Kinshasa as a genre painter. The Belgian gallerist Dierickx, then living in Leopoldville/Kinshasa, regularly bought works from Congo, later Zaire, and traded them in Europe together with works by other “popular” artists.

When the organizers of “Horizonte ’79” in Berlin wanted some of his works, D. had ordered about 30 paintings. What happened was that Chéri Samba sent 30 versions of one of his standard (genre) paintings of “Mami Wata”, the mythological siren. The Berlin exhibitors presented them all on one wall, creating a very modern installation of “multiples” – a fundamental misunderstanding.

It shows how the intervention of curators can create a false image of a particular local art culture.

The Parisian gallerist Jean-Marc Patras had a contract with Chéri Samba (around 1990) and did a lot to raise his profile in the art world. But there were competitors, and Patras couldn’t really control what was happening in Kinshasa, and Chéri Samba dealt with anyone who approached him, circumventing the terms of his contract.

Chéri Samba was the first contemporary African artist to be honored with a retrospective exhibition – “a Retrospective” – “Exposition retrospective” by the “Provinciaal Museum voor Moderne Kunst” in Ostende, Belgium: Chéri Samba. Le peintre populaire du Zaire, 21 octobre 1990 – 7 janvier 1991.

There is a review of the exhibition “Africa Explores”. (Meier-Rust 1993:219-227) The author admires the attempt to present African art, the modern art of an entire continent, with 133 works from 15 African countries. Strange is the lack of knowledge about the subject, the scope of Africa, its political, geographical and cultural set up:

” ‘Continent’ in this case means Black Africa, without South Africa, and with a strong concentration on West Africa and Zaire, hence in francophone Africa.” (Meier-Rust 1993:220)

How is it that the author does not know all the anglophone states in West Africa? Gambia, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Ghana, Nigeria (and part of Cameroon)?

Africa Explores could be considered a kind of predecessor of the Saint Louis project, and we can admit that the intervening quarter of a century has indeed improved the art of understanding, the art of representing the cultural specificities of the continent.

But whatever the shortcomings, these exhibitions definitely mark the arrival of modern African art on the European and American continents.

Chéri Samba was included in the Pigozzi Collection, assembled largely by André Magnin, and in his solo exhibition “J’aime Cheri Samba” at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain in 2004.

His works were also part of the exhibition at the Cartier Foundation in Paris in 2015 on the art of the Congo: Beauté Congo 1926-2015. Congo Kitoko.

The Musée Maillol in Paris presented a retrospective of more than 50 works by Chéri Samba from the collection of Jean Pigozzi in 1923/24: Chéri Samba dans la collection Jean Pigozzi. (Neutres/Whitelaw 2023)

The director of the Frankfurt Staedel art school, the late Kasper König (1943-2024), gave Chéri Samba an exhibition in his “Porticus” hall in 1992 (which later went to Munich in Bavaria) – together with a new publication on his oeuvre. (Bender 1992) The importance of this accompanying publication is that it takes seriously Chéri Samba’s claim that the written texts in the paintings are as important as the figurative parts. All the texts are translated in the catalog, something that is usually ignored.

The Saint Louis exhibition of Chéri Samba’s painting, titled “Hommage aux anciens createurs”, at least provides visitors with the complete text.

The “Coray” comment by Chéri Samba

What is “narrative” – a narrative is a narrative and as such nothing more, and far from being the truth. We must be careful not to take written messages at face value.

In 1994 Chéri Samba was invited by the Ethnological Museum of the University of Zurich in Switzerland to visit and create a work based on this experience. I had the privilege of accompanying the artist to the museum. The “original” painting resulting from this visit was published in the catalog/book edited by the then Africa curator Miklos Szalay entitled “Afrikanische Kunst aus der Sammlung Han Coray 1916-1928”, Munich (Prestel Verlag) pp. 50f.

Why did the Saint Louis Museum choose the Brussels private collector’s version? And not the “original” from the Zurich Museum?

The text in the Saint Louis catalog/book relies heavily on speculation, I would say that a new narrative is being created.

Ed. Wolfgang Bender

Chéri Samba’s practice of creating several versions of a given painting might have been worth creating an additional narrative about the treatment of African artists in a changing art market where partners do not respect the rules but still make money.

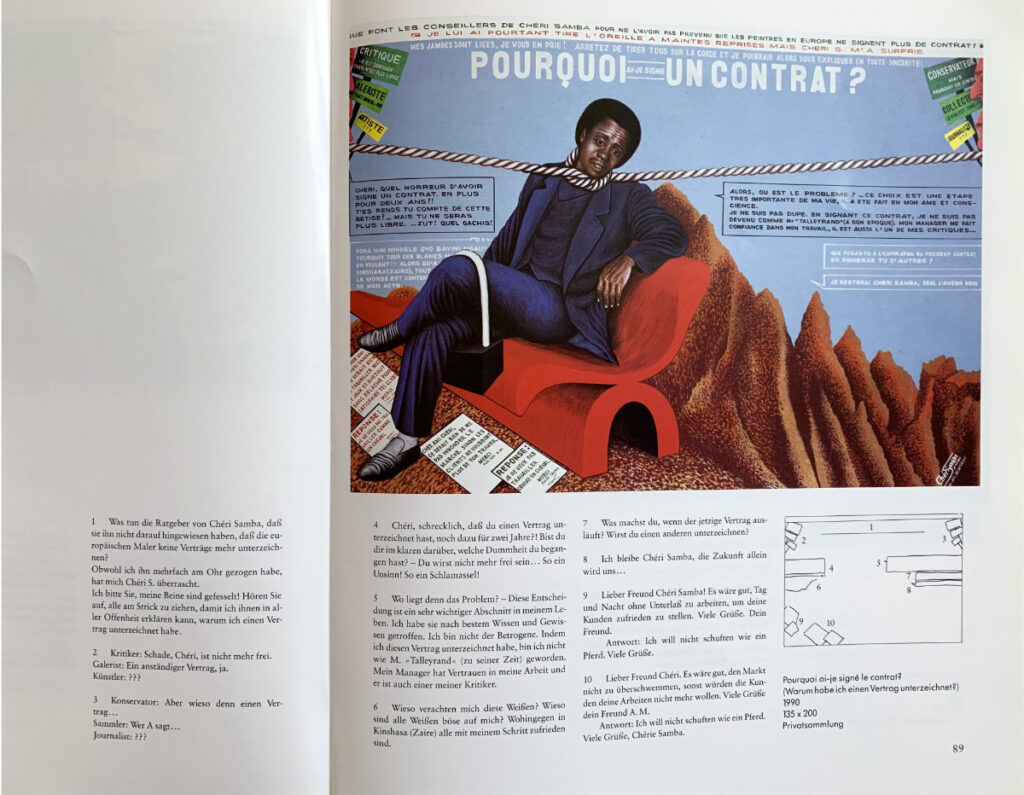

In this regard, it would have been particularly gratifying to take up the theme of the contract between a (European) gallerist and the artist by looking at and reading the painting by Chéri Samba entitled “Pourquois ai-je signé un contract?” from 1990 (135×200), reproduced in the catalog of the Portikus exhibition in Frankfurt am Main, West Germany. (pp. 88f.) Here the painter discusses the pros and cons of being bound by a contract. This could be seen as an allusion to the conflict between the gallerist Jean-Marc Patras in Paris, who had a contract with Chéri Samba, and the collector André Magnin, who went to Kinshasa to buy paintings directly from him, thus circumventing the contract and getting a better deal for Pigozzi. Chéri Samba defends himself by saying that he signed a contract, but that doesn’t mean as if he had been strangled by the gallerist. The painting shows the artist with a rope around his neck, drawn on one side by the gallerist and on the other by the collectors and journalists.

In fact Chéri Samba does express his surprise, that he is seen as if he was torn on two sides and not, what we would assume at first instance that he is strangled.

Chéri Samba in St.Louis

Chéri Samba is the ideal artist to study narrative. It is a pity that the Saint Louis Art Museum did not fully realize this. The tryptich (as in the present Hirmer catalog) as a pull-out page with the title “Quel avenir pour notre art?” from 1997 visually quotes the Zurich Museum painting. It shows that Chéri Samba practices an ongoing discourse. Too bad the exhibition missed this rare opportunity! (Magnin 2004: 91ff)

In fact, the latest publication on the work of Chéri Samba Chéri Samba dans la Collection Jean Pigozzi for the exhibition at the Musée Maillol in Paris in 2023/24 (Neutres/Whitelaw 2023), published in 2023, shows further versions of the Zurich Ethnological Museum of the University painting. There is one from 2008 in which the artist is positioned in the same way as a TV announcer, working on a list. Of inventory? Of the prices? The text in earlier versions has disappeared, leaving only the title ‘Hommage aux anciens createurs’, which is even repeated below the pictures on a painted frame like a caption with his name, all in capital letters: CHERI SAMBA: HOMMAGE AUX ANCIENS CREATEURS. Perhaps a gesture to the international public? Chéri Samba wants to be sure that he is in control of the representation of his work. Including himself in the caption, which is normally the job of the curators, shows a self-conscious attitude towards the galleries, the curators. He doesn’t want to leave it entirely to them to decide how to present him or his painting:

“Remplacer le statut d’objet du regard des autres par celui d’acteur de la representation, qu’elle soit scientifique, artistique, ou politique, c’est inverser les positions de regardeur et de regardé, de dominant et de dominé, et l’arrogance occidentale par l’aplomb du peintre africain demiurge. Chéri Samba est ce promethée modern qui vole le feu aux dieux à savoir le pouvoir de representation aux Occidentaux” (Neutres/Whitelaw 2023)

This book, which contains all the works by Chéri Samba that Jean Pigozzi bought, is like an inventory. This is also a sign of the status that Chéri Samba has reached.

The author of the section of the Hirmer book that contains the paragraphs on Chéri Samba is at the same time the person responsible for the entire exhibition, Nichole N. Bridges, who rightly admires Chéri Samba for his self-confidence in the face of traditional artists, seeing himself as a rightful heir.

She does not, as far as I can tell, discuss the fact that Chéri Samba recognizes the spiritual power still present in museum objects, but that his works are very modern and not spiritual in nature. They are political, often very much so, controversial and refreshing, they are of aesthetic quality, etc., but not spiritual. Often they are ironic or satirical to sarcastic, like the painting reproduced at the end of the book on p. 206 “Water Problem”.

Kathy Curnow’s chapter on the bronze panels of the Benin Palace is entitled “Narrative Resonance Through the Centuries. Esigie’s Youthful Challenges on Benin’s Throne” and is a kind of “preview” of her forthcoming book explaining the “visual autobiography” (p.135) of this Benin king who reigned between 1517 and the 1580s. It is a most impressive piece of scholarship.

The “modernity” link is a piece of wax cloth, a pagne, a “veritable wax” cloth. Unfortunately, we are not informed in such detail.

The explanation of “112 Fig.” begins with a questionable statement: “Edo artist”. Since this is an industrial product, this is a strange statement. It is indeed a “commemorative cloth”. The date given is “1980-81”. The reason for the date is given:

“The garment made from factory-printed cloth honors Oba Erediauwa’s mother at the time of her 1981 installation as iyoba.”

Most likely made during this period. There is no definitive proof. We are not informed about the factory and the usual imprint on the seam including the internal design number. It seems to be a “veritable wax” cloth, i.e. an industrial form of batik technique. The yellow lines could be the artificially created wax cracks. But it could also be “fake” wax, “imitation” wax as it is often called. You may have to examine the piece closely to get the answer. Who was the designer? Is it a two-color print? Blue and red?

Most likely. The photographic portrait inserted in the center and repeated – perhaps two or three times in a yard – is by a court photographer named Solomon Osagie Alonge.

The portrait is said to be that of Oba Erediauwa’s mother.

With these questions unanswered, how does one arrive at the connotation of “Edo artist”?

The study of Benin plaques is followed by a chapter on “Artists from Abomey, Artworks from Dahomey. From Language to Image,” by Gaelle Beaujean, curator of the Africa collection at the Musée du quai Branly in Paris.

The court of the kings of Dahomey had professional artists who “translated royal actions into graphic terms. (p. 142) These spoken-word professionals at the court, with their “constant concern for fixing history by” (p. 142) visual representation, worked with the lost wax technique, with textile appliqués, and with clay bas-reliefs.

Connecting the paintings of the contemporary Beninese artist Julien Sinzogan, entitled “Departure of the Spirits and Return of the Spirits II” (2008), showing large sailing ships from the period of “maritime trade in captive Africans” (p. 142) (trying to avoid the term “slave traders”, for which the Abomey kingdom was known, for capturing and selling!) with the depiction of the “boat” in palace art, “conjures up” the king Agaja in the early 18th century, whose emblem was also the “boat” (p.142).)

The famous Benin artist Cyprien Tokoudagba (1954-) created a series of rather large paintings inspired by the textile appliqués of the Abomey palace (Magnin 1991: 144-149; Gaudibert 1991:114). The caption note on p. 144 mentions in parentheses after “Sin titulo – without title”:

Emblemas de los Rayes de Abomey – Emblems of the Kings of Abomey. Etienne-Nugue, referring to the work of Jean Gabus 1967, reproduces in her book of 1984 (p. 190ff.) the “motifs and symbols” belonging to the various rulers of Abomey, starting with Gangnihessou (1620…), including Agadja (1708-1732): – bateau (houn), “le preneur de bateaux”.

In this case, too, we must ask ourselves why the Saint Louis museum did not choose the work of Cyprien Tokoudagba, since it is such an appropriate example of how a contemporary African artist takes up the famous motifs of the Abomey royal palace artists.

(Ashton 1993:230) Jocelyne Etienne-Nugue emphasizes the interconnectedness of all the images of the palace as one that all contain writing:

“On a souvent évoqué la valeur pictographique de cette “écriture” qui, en ce sens apparait comme tres modern. Ce sont en effet les memes symbols qui apparaissent, isolés ou sous forme de proverbs et de rébus, de sentences ou de voeux, dans toute les productions artistiques du royaume, véhiculant une forme de langage evident. Les bas-reliefs comme les tentures nous renseignent sur les différents règnes, leurs histoires et leurs traditions, de meme les portes en bois sculpté des palais don’t les décors sont parfois appliqués à la manière des tissus; les récades aux crosses diversement travaillées attestent de leur appartenance à tel ou out el roi, ou de leur function de messager ou de bourreau; les assens, les calebasses gravées,

les peintures murals, racontent, dans leur style, des histoires. Chaque signe, dans cet art, garde valeur de communication.” (Etienne-Nugue 1984: 195f.)

Indeed, the art of the Abomey palace is rich in narrative. An ideal corpus to fit the claim of the exhibition as a whole.

The third section of the catalog, entitled “Destinies,” begins with a contribution by the “independent” scholar Jan-Lodewijk Grootaers on “Divination as Narrative” – the role of artworks in oracular discourse.

The author is aware of the wide range of topics related to divination and therefore chooses:

“Here we will consider divination primarily as a verbal art with strong acoustic and visual components. In what follows, I will focus on African divination systems as techniques of communication and generators of narratives, and explore the discursive role of divinatory works of art” (p. 155). (p. 155) It is the “divinatory apparatus” that is the focus here, the divination baskets in Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Zambia. Among the Chokwe, the divination basket may contain “more than fifty small objects of various sizes, shapes, and materials” (p.155). These ingredients may be representations of humans or animals, may be of vegetable or mineral origin, and are all used in the divinatory process. Similar containers exist in other areas, such as the Congolese Luba.

The “oracular discourse” is also a sound event. The diviner’s voice may be high-pitched at times. Musical instruments may be used. Sometimes there are instruments used exclusively for the oracle performance, such as the Yoruba Ifa oracle, the iroke ivory horn “tapper”. It is used to “rhythmically” beat the Ifa tray – itself another ornate piece of art.

The artist Romuald Hazoumè (1962-) has been working extensively with Ifá since 1993. The catalog shows “Extraction” from 2009, acrylic and earth pigments on canvas with symbols used by the diviner. A fitting choice!

The exhibition catalog does not reveal whether there is music in the rooms.

As for the paraphernalia of a spiritual healer or diviner, there is a beautiful video clip by the South African pop star Yvonne Chaka Chaka (1965-) (Molefe 1997) from 1987. In “Sangoma” – which stands for spiritualists – we can observe a lady’s visit to a sangoma and the whole process of the examination. She presents the photographs of two lovers and wants to know which of them loves her seriously, and she gets a definite answer. (Chaka Chaka 1987)

“Graphic Scripts for Healing” is the title of a chapter with images of objects, organic materials, wood, metal, textiles, and drawings, all related to their function in healing or assisting healing.

Among them are two Ethiopian “Healing Scrolls” – the only illustration in the whole beautiful book production, I think, that is regrettably and unsatisfactorily too small. Another fold-out page would have been a pleasure to look at.

The caption to fig. 146 says: “Amhara or Tigrinya artist”. Why could this not have been clarified?

“Love. Let me count the ways” is the title of a chapter by Elyse Dianne Schaeffer of the Saint Louis Art Museum.

“In several sub-Saharan cultures, gifts between loved ones include visual representations of verbal messages. Often alluding to proverbs or poetic expressions, …” (p.183) These include the famous Zulu “love letters” of South Africa and the distinctive khanga printed cloth of the East African coast. Here at least the caption to fig. 156 says: “Rivatex/Rift Valley Textiles (founded 1975, Kenya)”.

The Kanga is an ideal subject for “narrative wisdom” and for storytelling! And the author has observed European contributions to this East African coastal fashion culture! And not only that, she has included contemporary discourses. I’m particularly happy about the dirt flap – she calls it a “mud flap” (pp. 159-163) – because for a long time I didn’t know anyone who had an open eye for it. In my exhibition of 1986 in Sierra Leone and from there to the Völkerkundemuseum in Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany, Popular Art from Sierra Leone (Bender 1987), I presented mud flaps for lorries and motorcycles as well as “lorry paintings”, i.e. the whole program of decorations around a lorry with specific motifs at specific places – not on metal, but on plywood. The only thing I miss here are the names of the painters.

She discusses the 2016 photographic triptych “Denkinesh: Birth on the Ground, Climbing, Standing” by Ethiopian artist Aida Muluneh, who refers to the famous paleoanthropological “Lucy” – not only called like that in the “West”! What about the “East”? – which in her view resembles the “past”, and the “Storage Rack Panel” by the South African Zizwezenyanga Qwabe. Belonging to the “past” she comes back to the Ghanaian Asafo flags. The long banner can be appreciated through the beautiful pull-out page.

For the “present”, she chose stills from a video film by Sammy Baloji from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

“The video conveys the history of the Pungulume region of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) by alternating between interviews with the chief and his elders, a conversation among the region’s sub-chiefs, clips from the 1912 film Panorama Star of Congo, and contemporary footage of the land itself.” (p.197) “Unfortunately, the mining displayed in the video has devastated both the mountains and the community of present-day DRC. Like large-scale and industrial mining elsewhere in the world, copper and cobalt mining in Pungulume contributes to the irreversible decline of biodiversity, the major pollution of waterways, and the permanent loss of water systems. In addition to these environmental casualties, cobalt mining in particular has led to multiple human rights violations in and around Pungulume. Ever-increasing demand for technology powered by cobalt (such as electric vehicles) has emboldened corporations to use any means necessary to pursue profits, resulting in forced evictions, child labor, and company-sponsored violence.” (p. 201)

Nigerian Sokari Douglas-Camp’s sculpture “Relative” is included. It denounces the oil spills caused by the global extractive industries. (p. 203) The painting “Water Problem” by Chéri Samba from 2004 – “Chéri Samba goes looking for water on the planet Mars” sitting on a rocket – refers to “the future”.

Elyse Dianne Schaeffer summarizes:

“American individualism instructs each person to fend for himself, and Samba’s response makes literal the ridiculousness of that proposition. (p. 206)

Compliments on a progressive attitude!

Bibliography

- Abiodun, Rowland; Henry Drewal and John Pemberton III 1991. Yoruba Art and Aesthetics. New York (Center for African Art), Zürich (Rietberg Museum).

- Agthe, Johanna 1990. Wegzeichen – Signs. Kunst aus Ostafrika 1974-1989/Art from East Africa 1974-1989. Sammlung 5: Afrika. Frankfurt am Main (Museum für Völkerkunde).

- Ashton, Dore 1993. „Zwei Hühner und eine Flasche Gin.“ Besprechung der Wanderausstellung „Africa Hoy“ (Las Palmas 1991) in: Kunstforum 122, pp. 228-231.

- Axt, Friedrich, El Hadji Moussa Babacar Sy (Hrsg.) 1989. Bildende Kunst der Gegenwart in Senegal / Anthologie des Arts Plastiques Contemporains au Senegal / Anthology of Contemporary Fine Arts in Senegal. Frankfurt am Main (Museum für Völkerkunde).

- Badsha, Farzanah 2015. „Hans Blum im Gespräch mit Farzanah Badsha,“ in: Mutumba, Yvette und Gabi Ngcobo (Hrsg.): A Labour of Love. Bielefeld. (pp. 278-281).

- Bargna, Ivan 2008. Afrika. Der schwarze Kontinent. Bildlexikon der Völker und Kulturen, herausgegeben von Ada Gabucci, Bd. 6. Berlin (Parthas Verlag).

- Beier, Ulli 1961. “Ibrahim El Salahi”. Black Orpheus (Ibadan) 10: 48-50, n.d.

- Beier, Ulli 1968. Contemporary Art in Africa. London (Pall Mall Press).

- Beier, Ulli 1980. Neue Kunst in Afrika. Berlin (Dietrich Reimer Verlag).

- Beier, Ulli 1982. Middle Art spricht über sich selbst. Bayreuth (Iwalewa-Haus).

- Bender, Wolfgang 1980. „Kunst und Kolonialismus in Nigeria“ in: Ulli Beier, Neue Kunst in Afrika. Berlin (Dietrich Reimer Verlag), S.11-21.