(This article was first published in 2000 on the website of AMA – African Music Archives.1

Prologue

The following article was written shortly after my return from Sierra Leone in summer 1986.2 Over several months I had been in Freetown to work on the safeguarding of the shellac discs in the Gramophone Library of the Sierra Leone Broadcasting Service (SLBS). The Project was funded by the West German Foreign Office in Bonn out of its cultural preservation budget.

The gramophone discs were played on a high quality machine and from there copied on to two reel-to-reel tape reorders simultaneously. This way one copy was to be used for the actual use of the broadcasting station whereas the other one went with me to Germny to be kept as an additional safety copy.

As the collection of the SLBS was of unique quality, comprising especially gramophone discs exclusively from Sierra Leone, the measure was taken after the director of SLBS had requested the assistance by the German government in 1984.

In 1990 a ferocious civil war had broken out in Sierra Leone, and rebels completely destroyed the radio station and with it the entire archive. Thus the copies in Germany were the only remains of the gramophone archive of SLBS. After the war the SLBS staff asked for a new copy of its shellac collection and our Foreign Office funded it again, as well a few years later another copy on CDs.

Even though the survey is from 1986 I consider it valuable for anybody into the research of record production of African music. It provides on the one hand an insight into what was produced at the time with artists from Sierra Leone, but it additionally informs us on the scope of music an anglophone West African radio station sent out on air!

By all joy about the documented collection we have to keep in mind, that any archive, and this included, is not complete, was never complete, and became less complete year by year. Shellac discs are breakable, they are worn out after intensive use. All that among other reasons made the collection a little bit like the “left over” of the period of the 1950s and 1960s.

Introduction

Very little research has been done in popular African music in general and even less in the area of the beginnings of commercial recordings. My particular interest is to look at period of the 1950s and early 60s when listening to gramophone records became an accepted entertainment. What music was being produced? Where was it coming from? What was the role the multinational record companies played in the African record market? Who were the musicians of that period? There are many more questions to ask, but to provide any answers at all the basic research has still to be done. The problems we face here are like those of any other research in the field of popular culture. There are no academic archives of the documents in question, popular culture has its own separate existence which we have to reconstruct like a puzzle. Even though at this time it is everywhere on the streets it soon disappears into oblivion, remaining in peoples memories and in rare commemorative items. This is what makes popular music research difficult, even more so in Africa where less written documents can be referred to. Some hints as to its existence could be found in such remarks as the following from the autobiography by a Lebanese from Sierra Leone, Farid Raymond Anthony, describing the situation in provincial Sierra Leone before the first World War:

Social life was limited. There were no radios to provide entertainment and only a few hand-wound gramophones using 78 r.p.m. records which were hard to get and were easily broken.

(Anthony 1980, p. 26)

Gramophones and shellac discs became an increasing important entertainment within the social class of western, i.e. Christian, educated Africans throughout the continent. Radio which started between the wars but really took off after the second World War contributed to the promotion of the record in general. In the rest of this article we have chosen the Sierra Leone Broadcasting Station with its gramophone library as an example of the world of African shellac discs, their production and consumption.

Sierra Leone is one of the smaller African nations in the West of West Africa and because of its capital Freetown, founded in 1787 to give freed slaves a new home, it had an early and intensive experience with the western Christian education and values3.

The History of SLBS

The Sierra Leone Broadcasting Service began its operation in 1955 (Decker 1956,p.166). It was preceded by a wired broadcasting service, known as “rediffusion” system. This worked as follows:

a central wireless receiving set was provided by Government which was powerful enough to receive broadcasts from most parts of the world. Connections were made from this set to contributors’ homes by telephone wires connected to the smaller receiving sets or loud speakers in these homes. Local events could also be transmitted live from the broadcasting centre. The officer in charge of this station was responsible for choosing the programmes or country from which the broadcast was coming and then relaying them to the loudspeakers in homes which already had telephones, and the fee payable for this convenience was £ 2.12. 0d per year .

(Anthony 1980, p. 79)

This service had been introduced in 1934 by Sir Arnold Hodson, the “Sunshine Governor” ( who according to C. During arrived on the HM Aba). He had started a similar service as a governor of the Falkland Islands (Findlay 1975, p.13). On the 7th May 1934 at the Wilberforce Memorial Hall the event took place:

True to expectations exactly at 7p.m. a hush fell on the listeners and eyes turned towards the various loud speakers as they crackled into life and the voice of His Excellency, Governor Arnold Hodson came loud and clear – “Ladies and Gentlemen, I have been looking forward to this evening for a long time with intense pleasure. I consider, and I think you will agree with me, that the new broadcasting service opens up a new vista of life to all of us who live in Freetown…. . We press a button and are transported to London; again we press it and we hear grand opera from Berlin….” A few minutes later the Governor turned up at the Hall to receive a loud acclamation .

(Anthony 1980,p. 79)

This was shortly before Hodson became governor of the Gold Coast where he started the second rediffusion system in West Africa (Decker 1956, p.167). But the rediffusion system in Sierra Leone persevered although Professor Eldred Jones comments that:

Rediffusion by wire in a city full of trees and liable to heavy rainy season storms was a very vulnerable service, and the funny little box with its single control knob frequently went dead, or fell to whispering its message.

(Findlay 1975, p.21)

Music by wire included programmes – live or recorded – from artists like Ralph Wright, “the multi-instrumentalist” (C. During 1984). As Eldred Jones mentions:

Much later this was to prove specially frustrating for our house hold because one of my sisters sang, and often featured in Ralph Wright’s ‘Variety Time’ programmes. When nothing came out of the box or when it merely crackled and distorted my sister’s efforts we stopped just short of assaulting the offending loudspeaker.

(Findlay 1975, p.21)

‘Variety Time’, introduced in July 1945 is said to have been one of the most popular features ‘on the African air’. Twice a week the BBC was faded out at Freetown to make way for Ralph Wright and his ‘Radio Discoveries’.

…twice a week Africans crowd eagerly round all available receivers – for the success of the programme has been quite spectacular. Ralph Wright, the Compere-Producer, is a versatile musician , and when he is not dealing with legal problems (he is a Law Clerk) he is in the rehearsal rooms grooming his performers, who are all, like himself, young amateurs. Despite the big names of Radio available from the B.B.C. by the turning of a switch the African listener continues to look forward to “Variety Time” with real pleasure and anticipation.

(West African Review, Dec. 1947, p. 1444)

‘Variety Time’ was in fact Lionel Millar’s creation: if he remembers correctly, although this is open to dispute if set against the report above of West African Review’s:

…what I do remember is that sometime in 1947 the Public Relations Offices asked me to do a musical programme on the Freetown Rediffusion Service. I presume I was selected because I had a small idea of music and I found myself in the company of Ralph Wright, Chris Walker, my sister Enid Millar, as she then was, and a few others whose names I cannot now remember. That first “Variety Time” programme was considered a success and I sang and played “Apple Blossom Time” with Chris Walker and “Sweetie Boisie” with my sister Enid. From that time “Variety Time” flourished into a recognised and memorable programme for about fifteen years and the artists were varied and many.

(Findlay 1975, p.31)

There was obviously a keen interest in programmes of Sierra Leone music which originated in Sierra Leone. The BBC could not satisfy this interest, however much they tried. The British were sensitive enough to react to that changing situation.

[And if we have to take a popular designation serious]. In contrast to the West African Review’s good will promotion article, the rediffusion system was not an undisputed institution among the populace. The West African Review, a publication financed by the Elder Dempster shipping line, had only one rationale, which was that to serve the colonial economy right. Ideologically it’s role was support anything that spread positiv and good mood among colonial subjects. Mr. George Tregson-Roberts, at one time Chief Social Development Officer, who had his ears to the ground mentions the “rather irreverent” voice of the people calling the rediffusion sets “Congosa Boxes“. Kongosa is listed in the Krio-English Dictionary as standing for gossip and is derived from a Twi word meaning ‘falsehood, deceit, hypocrisy’ (Fyle and Jones 1980, p. 181). This could be an apt indication of the people’s wit and power of analysis of the BBCs role as a radio station which represented the Government’s side within the colonial situation.

The popular assessment of colonial radio contrasts substantially with the ‘official’ view as expressed by the SLBS’ first Director of Broadcasting Leslie A. Perowne, who was seconded to Freetown from the BBC in 1956. He believed in the myth of an objective Radio station:

That is one reason why the BBC is so respected throughout the world; its news is objective and the listener knows it .

(Findlay1975, p. 14)

During the post-war period British Colonial policy was generally to develop broadcasting in Africa in order to intensify the education and information of the populations concerned. This served a twofold purpose. On the one hand it was a demand by the growing section of politically aware people in the colonies working towards self government to have their own radio stations as well as a medium for the British to strengthen their own hold with the help of modern communication media.

In 1949 the Sierra Leone Government was one of a number of Colonial Governments who were informed that the Colonial Development and Welfare Fund would spend about £ 1.000.000 to develop broadcasting in the Colonies. Sierra Leone received a grant of £ 23.000, which paid for the transmitter and the cost of expanding the Freetown studios.

(Decker 1956, p. 167).”

In its initial stages, i.e. before the SLBS was headed by a Department of Broadcasting, it was run by the Railway Department, the Public Relations Department and P&T.

The Freetown Rediffusion System functioned parallel to the SLBS and was closed down only in 1963. The Gramophone Library – according to its present librarian Mr. Emanuel O. Bedford – started its official functions in January 1958.

By mid 1958 the sum of £ 3100 was voted out of a grant to Broadcasting for the ordering of Commercial Gramophone records through Crown Agents, and local purchases.

(Bedford n.d., p.1).

The library was started by Mrs. Catherine Haye ( Hungarian born). One can guess how important the library was considered by looking at a photograph taken during the early days of SLBS showing the “usual Monday morning conference in session” with all the members of staff responsible for running the radio including “the first Gramophone Library Assistant Mrs. Catherine Haye” (Findlay 1975, p. 44). In another photograph we can see her in the “First Gramophone Records and Tapes room – the nucleus of the S.L.B.S.” Library together with John Akar, “First Sierra Leonean Director” and Lionel Millar “then Programme Planner“(Findlay 1975, p.44). The Publication “Sierra Leone Broadcasting Service – 40 Years of Broadcasting, 1934-74” does not mention the library on any other page.

By 1976 the Library had “well over 15.000 records and a little over 1000 tapes in the archive” (Bedford n.d., p.1). However in the following years SLBS was not able to purchase any new records. The reason given for this is 1.) the general economic situation and the connected problems with foreign exchange and 2.) the absence of both record shops in the country and record production (Bedford n.d., p.1 and p.2).

The shellac disc collection

In 1986 the SLBS gramophone library possessed 716 shellac discs with African music. There are shellac discs with non-African music also, but these we leave aside here. They are all stored in a special record room with potential air condition. The records themselves are all in uniform brown carton covers. The degree of preservation is different due to either more or less frequent use or position of storage. Stocktaking takes place every two years. This means that all discs will be taken out by the library assistants and checked against a master list. This action in itself may be of risk for the preservation of these delicate products. Some might not survive the undertaking. This means that with each stocktaking several losses occur. On the other hand it is exactly this administrative procedure which might in part be responsible for the conservation of these shellac discs that are absolutely of no practical use any longer.

In 1984 and probably for some years earlier there was no listening facility for shellac discs in the library or anywhere else at SLBS. This might have been a positive condition for the preservation because it left this part of the room untouched. The records are sorted according to companies or labels and then numerically.

From the total amount of 716 gramophone records 225 are Sierra Leonean music, which is just below a third of the whole collection. The other two thirds are from other parts of Africa. In that section records from former British territories form the larger part. From francophone Africa there is only the then Congo of significance. Here are the figures according to countries:

| Sierra Leone | 225 |

| Southern Africa | 65 |

| Ghana | 112 |

| Malawi | 2 |

| Nigeria | 89 |

| Kenya | 9 |

| Uganda | 11 |

| Zaire | 203 |

From this figure we can see that the total number of records from Sierra Leone more or less equals the records from the Congo and from the other former British West African territories. This points out the sympathies that existed at that time in Freetown towards the music from outside. Congo music was rated very high up. West African music people in Freetown in particular loved as for a great proportion of the population this was music from their former homelands. That there are records from Southern Africa and a few from East Africa is definitely the case because of the link between British territories within Africa.

Congo/Zaire music

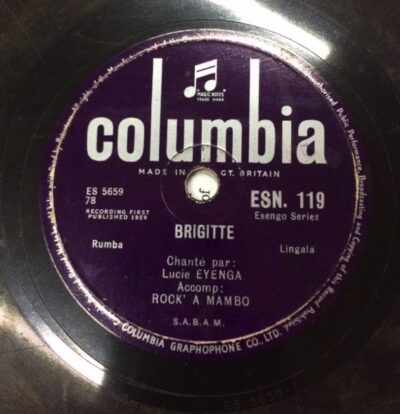

A good number of the Zaire music does come from South African Gallotone label which published various Katanga (now Shaba) province guitarists in the later fifties, among them Mwenda Jean Bosco, Mwenda wa Bayeke. He was initially recorded on one of Hugh Tracey’s recording expeditions and one of his songs was later even given the Osborn Award in South Africa4. Nearly 100 shellac discs were recorded by Gallotone with him and it is no surprise then, that there are 15 discs by Bosco in the SLBS and 8 records by another Katanga guitarist Losta Abelo. The airplay of these records from South Africa or from the Congo was responsible for the wide acquaintance of artists like Bosco in countries that are far from their own country and by people who did not even understand his lyrics. This again led to popular reinterpretations of song texts5. From the Congo the most famous artists were among the records of the archive and were put on the air as well. The Ngoma label was one of the first record companies in Leopoldville (today Kinshasa) to start with the production of Congolese music. HMV (His Master’s Voice) obviously licensed titles from another famous early label, the Loningisa label. Columbia – of EMI too – seems to have taken its recording from the Esengo label.

Among the leading musicians and singers were G. Edouard, M. Oliveira, H. Freitas, J. Bokelo, L. Bukasa, A. Wendo and already most of the musicians of later fame, like J. Kabasele, Franco Luambo Makiadi, Nico and Rochereau.

Of interest too, the Congolese Opika label had Nigerian and Ghanaian bands in its programme and one wants to know, for whom they were intended to be sold for. Were they for the export to Nigeria, or was there a market for Nigerian or Ghanian music in the Congo? Among their artists were such eminent market leaders as Bobby Benson from Nigeria.

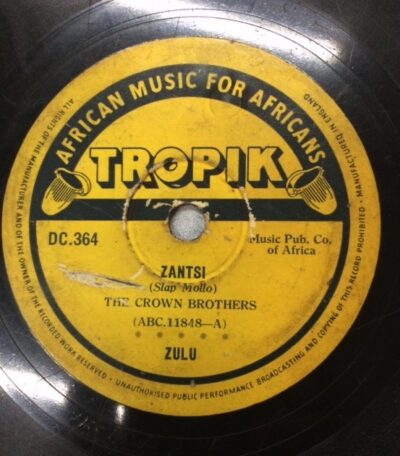

Southern Africa

A number of record companies besides Gallo do have music from Southern Africa on their records, there is Tropik, Hit and Troubadour. Marketwise the whole of British Central and Southern Africa constituted one single area. Like Gallotone included Bosco in their repertoire the other companies go as far north as even Kenya. Troubadour in addition did produce West African records. But it seems that what concerns their selection of material is that they only include ‘modern’ music.

East Africa

Besides a few South African companies with records from East Africa there are only a few records from the African Gramophone Stores from Nairobi.

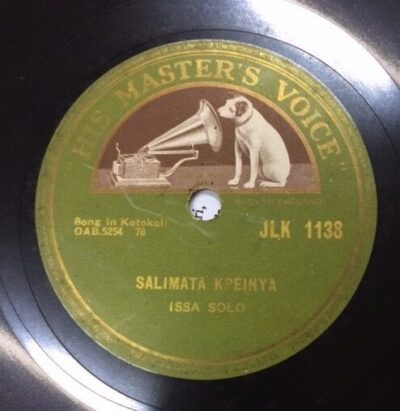

West Africa

The multinational record companies are represented here with a number of labels. From Decca the ‘Yellow Label’ series with West African music is present – however the samples carry a brownish label marked with ‘Not for Sale‘. May be the series was given to SLBS for promotion purposes as ‘Complimentary Copies’? The Yellow Label series comprise music from Sierra Leone, Nigeria and Ghana – the former British West Africa – leaving aside Gambia. There were in all 121 shellac discs of the Yellow Label in the SLBS library. This is not all that much compared with the collection of Anthony King in the National Sound Archives in London which counts 476 numbers. What is surprising though is, that there are hardly any numbers from the SLBS in the NSA collection. If Decca published more than 3000 gramophone discs with West African music on the Yellow Label, there is still a large gap to fill to get a complete picture of this series. SLBS and NSA together make up only 600, i.e. only a fifth of the whole production. From EMI there is the HMV olive label ‘JLK’ series with Ghanaian music only and the yellow label ‘J.Z.’ series with music from Sierra Leone, Ghana and Nigeria. If the numbers were all published there might well have been over 6000 records alone! 16 records then with the yellow and 50 with the olive label look very poor indeed.

Labels of Multinational Companies and by Countries

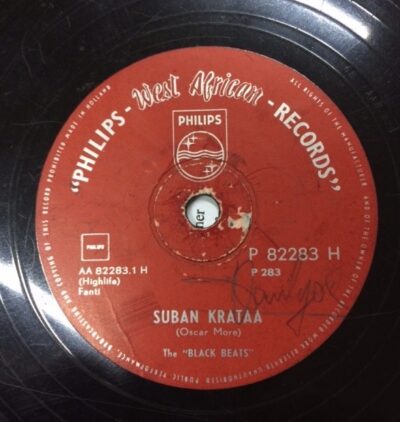

Philips

There must been hundreds of the ‘Philips West African Records‘ series, but only one was in the SLBS library.

Local labels

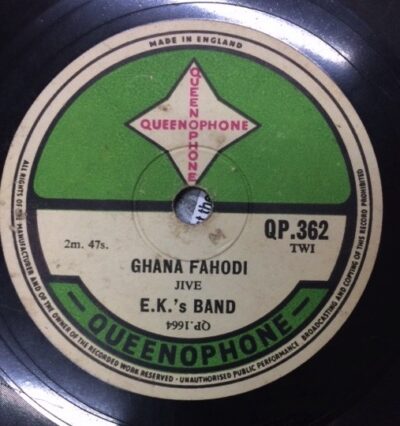

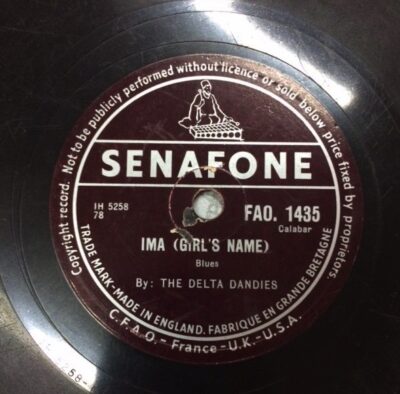

There are a few of the comparatively small local companies in the collection. From Nigeria e.g. Patsol from Calabar or Nigerphone from Onitsha. In Ghana there was Queenophone and though only a few records are in SLBS the numbers suggest there might have been a few hundreds too. Senafone label did produce Ghanaian and Nigerian music for the chain of shops called C.F.A.O. (Compagnie Francaise de l’Afrique Occidentale).

Records from Sierra Leone

Record Companies in Sierra Leone

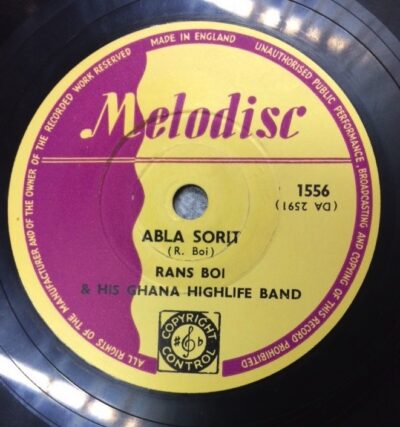

From those 225 records with Sierra Leone music only 33 do come from larger international companies. Decca had a few records on its Yellow Label, among them E. Calender and Scrubbs, as well as Sallia Koroma, Tejan-Sie and a number of others – traditional and modern bands, 19 altogether. By far not everything that Decca produced from Sierra Leone is in the SLBS library. To answer the question, if they ever had been there or not, needs an additional investigation into the books. From Columbia‘s blue label 3 records contain Sierra Leone music. HMV published in its J.Z. yellow label 8 discs from Sierra Leone, including Calender and Ali Ganda. Melodisc had 3 discs from Sierra Leone with Ali Ganda and Tejan-Sie among them.

We are still far from knowing the total production of Sierra Leone music by international recording companies. The Decca West Africa catalogue from 1962 lists 3 Ebenezer Calender records ( WA 2501,WA 2502, WA 2504), 2 by Tejan-Sie ( WA 2671, WA 2673) and one each by ‘Kande & His Kondi Singers’ ( WA 2663) and by ‘Kamara & His Gbulu’ ( WA 2705) (DECCA 1962). None of these were listed in the catalogue of the following year, 1963 (DECCA 1963).

Not even one record was in the library From the above listed Calender records.. WA 2502 is the most famous of Calender’s records with the song ‘Fire, Fire, Fire‘ – but this too was not there.

It seems from the records of Sierra Leone that appeared on international labels, that the record production in Sierra Leone was on a very low level. This view does prove wrong as soon as we do get the opportunity to look into the local production. Until recently there was no awareness of these productions lacking any knowledge of them on the side of the outside observer. This is not only true for Sierra Leone but for all African music6.

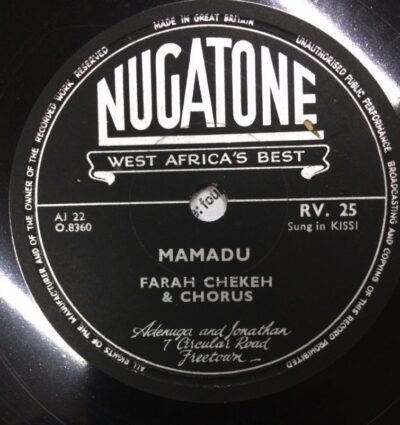

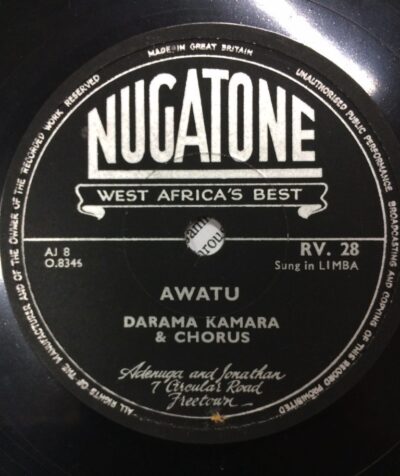

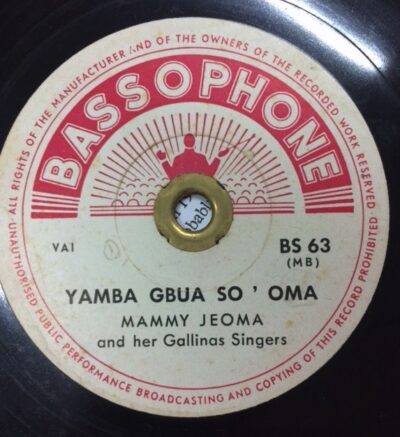

In Freetown – and in Sierra Leone record production was to the present state of knowledge limited to Freetown – there were two larger record producers during the 1950s and early 60s, Adenuga and Jonathan was the one and the Bahsoon Brothers the other. Both had their respective labels, Nugatone and Bassophone.

Nugatone

Jonathan Adenuga, a Yoruba from Nigeria having studied at the then famous British West African institution of higher learning, the Fourah Bay College – now the University of Sierra Leone, had started a record business. That was on 7, Circular Rd., he later moved to 18, Goderich Street (this new address is on all the records beginning with the ‘Independence’ series.) to expand his business. In his shop he sold shellac discs he imported as well as his own productions. Chris During said, that he was in fact the main importer of the Ngoma label from the Congo.

Adenuga himself was even singing on a number of his own recordings, e.g. on the Nugatone AA 36, ‘Jiving Marie Calypso’ by the band ‘The Freetown Darkies’ (Bender 1988)7. According to Chris During Jonathan Adenuga always grouped the same musicians with a few changes into new bands, giving them new names. In this way it appeared as if there were so many different groups signed on with him, but in fact they were mostly the same musicians (C. During 1984). Another of Adenugas creations is the ‘Freetown’s Leading Sextet’ (Bender 1988). He did the recordings in his shop’s backroom. But he later used the SLBS studio for recordings. After 1964/65 Chris During did recordings for Adenuga in the SLBS studio (C. During 1984). Then he sent his tapes to England for pressing and got them shipped back to Freetown. Adenuga had an amazing variety of titles to offer. There are Christian and Muslim religious records, traditional and modern groups with all kinds of songs and dances (Bender 1988). He had 93 different artists on 162 records, that is all SLBS has. What his whole list was can roughly be guessed from the numbers. The calculation can only be based on the highest number available of each series. The AA series up to 150, the AB to 9, the BB to 130, the FA series to 33, the NU to 111, the REL to 3, the RV to 35 and finally the SAL to 15. Altogether this accounts for 486 records minimum of which only 162 are at SLBS, a third.

Adenuga was an important institution in what concerns Sierra Leone music. On one of his record jackets the following is printed:

———————————-

NUGATONE

FOR THOSE WHO WANT

THE BEST

At the Sierra Leone Nugatone artists topped

Festival of the Arts the polls with the very BEST

6th-14th December 1957 songs – the most SUPERB

orchestration – the most

IMPRESSIVE performance.

NUGATONE

VOICE OF SIERRA LEONE

WEST AFRICA’S BEST

———————————-

Among the 162 Nugatone records in SLBS, 126 are recordings of traditional music, only a mere 36 are modern bands. This contradicts the common assumption, that recorded music, that music in the area of modern media means automatically a predominance of modern music as well. Nketia once remarked in view of the situation on the Gold Coast:

The bulk of commercial recordings are in the new style…

(Nketia 1956, p. 199)

But Nketia does not provide us with an overview if the whole record production in the then Goldcoast. As far as we can judge his remarks, he refers mainly to the records of the international record companies, which in fact have devoted more attention towards modern music.

After Adenuga died the shop was closed and his relatives returned to Nigeria.

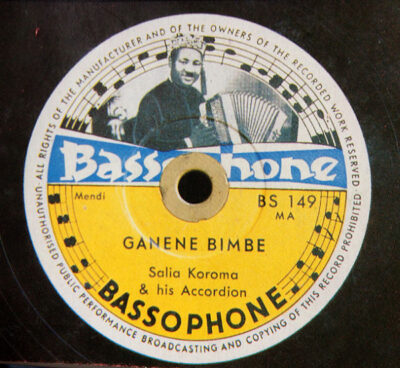

Bassophone

The Bahsoon brothers are a large Syrian trading company. Abdallah Bahsoon, now residing in Ivory Coast, the younger brother of Alhaji Adib Bahsoon, was born in 1938. The following information is very tentative and has to be crosschecked before final acceptance! The years are not clear too and the chronological sequence is not necessarily so.

Together with a Lebanese Samir Kobaise he ( Abdallah Bahsoon, W.B.) went into the record business “out of personal loving of the African music“. The date is not definitely known – but a date sometimes during the 50s might be right. The shop in No.4, Regent Street was probably closed in 1975. They all lived in No. 12 Regent Street and there the recordings were made. The recording machine had 7 1/2 speed and was probably an E Marconi. One or two microphones were used. £ 100 or £ 150 were paid for a tape of 3hrs. Then the tape was sent to Germany or later to France. The records cost in the shop 2 to 3 £. It was not possible to find out if this relates to 45rpm singles or the earlier 78s – as there are in fact singles labelled ‘Made in France’ from Bassophone.

The record shop that was the main outlet for the Bahsoon Brothers label Bassophone was the ‘Records Palace’ at no. 6 Water Street, Freetown. This name for a record shop does show how precious records were regarded. This definitely was open when shellac discs were sold, as there are jackets with its name that belong to Bassophone records.

The selection that the Bahsoon Brothers took was similar to Adenuga. But Bassophone was a smaller label than Nugatone. According to the highest number in the SLBS collection there were only 223, off these 51 are with SLBS – this is below 1/4 of the total. Similar with Adenuga it is fact that traditional songs are in the majority.

As long as we have not acquired a complete picture of the records published by the respective companies it is questionable to really make any assumptions on the selections made by the producers. The records that are in the SLBS collection could be the selection of the librarian who bought them, they could be free promotion copies or they could also be just what is left over by now, years after they have been in vogue. The most beloved ones, the real hits, might have been used so often that they were run down or because they were used so often they were likely to have been broken. The other possibility is that they disappeared into private possession, at the time when people were keen to have them or later when collectors viewed them as rare items. All these probabilities taken together might result in a gramophone library to be seen as a negative impression of what people specially prefered at a particular time. Therefore we have to be very cautious in our assumptions or deductions through looking at the stock of a collection. With an archive alone we can not make any valid statements about the taste of the public at a particular time. To work with the remaining stock would be the only way. To interview contemporaries, producers as well as consumers.

With Nugatone as well as Bassophone or any other record company or label in Freetown there is a complete absence of published documents related to the record production. There are no catalogues, they probably never have been printed any, or handouts, posters etc. Nothing has been found till today. Nketia did also draw the attention to this problem:

None of the firms appears to issue proper catalogues of records for the benefit of buyers. Cyclostyles lists of records in stock are however issued by some of them periodically for their shops.

(Nketia 1956, p.197)

Nketia refers here to the following record companies: HMV, Decca, Parlophone, Senaphone, Queenophone and Kwahu Waga. May be there were cyclostyled lists in Freetown too, but they have not been discouvered yet.

What has been found so far though are bills by the record intermediaries especially two West German commercial agents that were commissioned with the job to organize the manufacture of the records off the Sierra Leone tapes, the companies Büchting and Reining.

Here are the copies of two bills by Walter Reining for the pressing and shipping of 78rpm gramophone records from Sierra Leone to West Germany and back including the printing of labels and jackets.

1961 Bassophone Records CIF Price 1/8 Store 2/6

Walter Reining

Rchng. No. 61335 28th. 4 1961

vOrder BB 551

500 Bassophone Records 78rpm, 10"

No. SR 205

at sh 1/8 per record 151 Kilo

incl. Bassophone record bags

incl. two-coloured labels and packing

CIF Freetown £ stlg. 41/13/4

CIF value

41/13/4 16/13/4

Duty 16/13/4

3/8/- Port 8/3 Labourer 2/- Bank Charges 15/3

Total 61/14/8

Walter Reining

invoice No. 61239 23rd of March 1961

7 cases

1400 Bassophone Records, 78 rpm , 10"

1000 records No. SR 205 A/B

50 records No. BS 16, BS 32, BS 10

No. BS 49, BS 40, BS 11

100 records No. BS 221

at sh 1/8

incl. Bassophone bags

incl. two-coloured labels

incl. packing

£ stlg. 116.13.4

duty 46/13/4

The disc with the number SR 205 seems to have been a best seller as it was ordered twice in relatively short intervals, once in March with 1000 copies and again in April with another 500. Unluckily until now we do not know what record this is. But at least we have the whole sale price at sh 1/8 for the Bahsoon Brothers as new information. We also have an indication of the quantities of orders normally carried out. The majority of the records ordered in march were in 50 copies each. One is in 100 each. This is BS 221 and it is one disc that is in the SLBS library as well. It is a record from the famous Mende accordion player Salia Koroma. The song titles are on A-side ‘Domaya Ya’ and on B-side ‘Yngndu’. This information gives us at least an idea in what quantities a recording by a well established musician was ordered. 100 copies was obviously not bad, compared to the 50 each with the 6 remaining ones. SR 205 again is a record totally exceeding the ordinary quantity. In the present difficult situation it is of utmost importance to find documents like these bills. This is the only way to put our research in African music on a sound foundation.

Musicians

Similar problems like in the search for records or information on record production come up when trying to find out who were the artists that recorded these shellac discs. From those numerous musicians and singers where only two as examples; one more modern singer and one traditional accordion player and singer. The first is Tejan-Sie from Freetown and the second is Salia Koroma from Kenema.

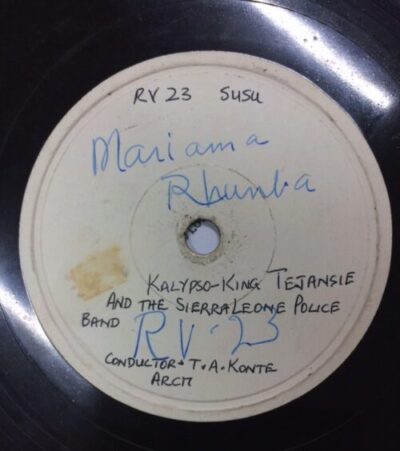

Tejan-Sie

Tejan-Sie as he is portrayed (in short) by his friend Chris During:

Tejan-Sie was born in 1927 in Freetown. He visited the Samaria Amalgamated School at Wellington Street, later he went to St. Edwards and then to the Methodist Boys High School. He was a very good footballer and cricketer. He had a beautiful voice which made him the blue eyed boy of Professor Greywood, the music master of MBHS. He was solo treble singer in the professor’s 100 voices choir and sang in churches throughout the length and breadth of Sierra Leone. After School he worked in the Sierra Leone Railways at which he formed his Calypso Band. With him playing the guitar and Ukelele Banjo. Of course he was also the lead singer and composed several songs. In the early 50s Sierra Leone had Self- Government and party politics came into being. Tejan-Sie joined the SLPP (Sierra Leone Peoples’ Party) and his band and talents were used to campaign for the party. When the party won the first General Elections he was given a scholarship to study speech and drama at Rose Bruford College in Kent, England. This was in 1959. He was very successful in Britain. He came back to Sierra Leone in 1964 to find great changes in the political scene. Although the SLPP was still in power – but the people he met did not know him – so he lost his popularity and political influence. This affected him both physically and mentally. His mother was a Christian and his father a devout Muslim. He was a Christian until he left school, when he became a Muslim. Besides his voive – peculiar to himself alone – he was an accomplished showman and very friendly indeed. He died in 1977.

(C. During, letter 23rd. march 1987)

One of the famous songs by Tejan-Sie and the Sierra Leone Police Band was his Welcome To The Queen. Tejan-Sie as a Calypsonian responded to what was going on in his days. The Queens visit to Sierra Leone was long expected for it was postponed for two years. In any case, the song too must have been ready for quite some time in advance to allow its appropriate release. It might not have been a coincidence, that ‘Welcome to the Queen’ (on Nugatone RV 1) is only pressed on B – side of this particular shellac disc; whereas ‘Farewell’ is on A – side! Tejan-Sie is singing. The accompaniment by the Sierra Leone Police Band conducted by T. A. Konteh includes a drum-set, a bombardon (to provide for the bass), trumpets and more percussion. The rhythm according to Chris During, is a typical Maringa, a Maringa-Gumbe!

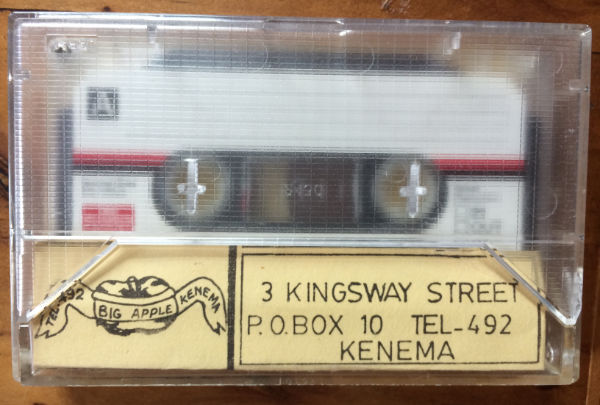

Salia Koroma

Salia Koroma is one of the best known musicians in Sierra Leone today. Especially after the death of Ebenzer Calender on Good Friday 1985, he belongs to the few that have survived the 1950s when he like Calender were already in established capacities8. Salia Koroma:

I was born in 1903. I was nine years of age when I started to play the accordion. Yes, I tried, I didn’t know how to play it. I tried on my own, trying to copy from my colleagues around. I went to wherever I heard of festivities, particularly Bundo ceremonies. I went in search of places of entertainment, just to be able to learn how to play the accordion. My father had told me that if I did not play the accordion he would curse me. So in spite of the difficulties I had to go through learning how to play the accordion – because I was afraid of the curse my father would put on me, I persevered. After some time my father began to teach people how to play the accordion. But he did not like teaching me because he was such a severe man. He said, “If I teach you the art of playing the accordion I might beat you to death before you could know how to play it. Instead, I will give the task of teaching you to my apprentices. You know I am a hard-hearted man”. I continued to learn on my own. Whenever one got spoilt my father always replaced it with a new one.

( Salia Koroma 1985, p. 8)

Salia thus became one of the most favoured Mende singer and players. From the 1950s onwards he did recordings. There are many 78rpm shellac discs that have been published and when the period of records was over cassettes were being recorded with him. One cassette bought in 1984 was numbered ’38’, ‘Saliah Koroma 38‘ and was published by a company called Big Apple from Kenema. Here now we have the unique opportunity to analyse the music by one Mende musician over a period of 40 to 50 years. A study of Salia would be a fruitful undertaking for any musicologist. A book about him would be a long needed venture. This would then be a fitting irony to his nearly proverbial expression: I know no book but book know me! This was to say, even if I did not attend school, i.e. even though that I am not able to read and write, I am knowledgable, I am educated – in my way.

On Ganene Bimbe, Salia Koroma & His Accordion ( BS 48 ) sings a Mende song in which he stresses the allegory of the new dress, which in spite of its love by the owner will either get torn or abandoned one day. This allows to dispute believes in the endlessness and permanance of artificial situations. Salia refers to ‘Janene’ as (not clear) a personification of the fast individual who may tend to rely on his fastness to avoid problems, but… money comes into play. Salia believes that money should serve the owner as well as the needy.

(content told by M.Kallon, Bonn)

Conclusion

The main surprise encountering the SLBS library was, that there did exist many local labels in Africa throughout the continent. Local labels that did not live for long but had a considerable role to play within the history of modern African music. These local labels rarely reached the European markets or entered gramophone record libraries. As they were only technically manufactured in Europe and tapes were sent there and the finished records were sent back to Africa, they did not really touch Europe at all. There were labels like Nigerphone from Onitsha in Nigeria that produced hundreds of records but were never really given credit for that in the history of African Music. Patsol too was a small company in Calabar, the most southeastern spot of Nigeria. There were many more and many more will have to be discovered in the next few years. The Radio archives of the particular states will be the best suitable place to look for all these labels yet unknown.

That is why the collection of SLBS is most interesting, not only in view of the different labels with music from all over Africa, but mainly because of the small labels of local origins with their often long repertoire list – of hundreds of productions!

These entrepreneurs were right on the spot of the local music scene. They did not have to rely on any ‘informants’ as most of the multinationals have to. They themselves knew the local scene. They knew what bands they wanted to feature, what they would be able to sell. That is why for some of the large companies these small firms only did the scouting job for them. Like in the case of Ebenezer Calender’s ‘Double Decker Bus’ song that was originally recorded by somebody else for the local Attalah label only to be copied by Calender for Decca West Africa ( Bender 1989, 56ff.). The local business men did everything to please their customers. That is why the variety of their labels is often of a wide range. The most important issue may have been the producers presence in the country and the ability to react quickly to new demands. Even though there were technical limits to the speed of ‘reaction’ because of the long postal routes. This only changed when the first record companies started to operate in Africa, e.g. Nigerphone in Onitsha , Nigeria.

Bibliography

- Anthony, Farid Raymond. 1980 Sawpit Boy. Freetown.

- Bedford, Emanuel O. n.d. The Role of The Gramophone Library. In: The Sierra Leone Broadcasting Service. 3 pp. Typescript.

- Bender, Wolfgang (ed.). 1984. “Songs by Ebenezer Calender. in Krio and English from Freetown – Sierra Leone”. Transcription and Translation: Alex Johnson. Song Texts of African Popular Music, No.2, 69 pp. Bayreuth.

- Bender, Wolfgang. 1988. Sierra Leone Music – West African Gramophone Records recorded at Freetown in the 1950s and early 60s. LP 33rpm, 12″,Zensor ZS 41, Cass. ZS 43, Notes. 33 pp.

- Bender, Wolfgang. 1989. “Ebenezer Calender – An Appraisal”. In: Bayreuth African Studies 9, W.Bender (ed.). Perspectives on African Music; 1989. Bayreuth. pp. 43-68.

- Calender, Ebenezer. 1985. Krio Songs. Stories and Songs From Sierra Leone, 1. People’s Educational Association of Sierra Leone. Freetown

- Decker, Thomas. 1956. “This is Freetown Calling”. The Story of Direct Broadcast in Sierra Leone. In: Sierra Leone Studies, n.s. 7, feb. 1956, pp. 166-168.

- During, Chris. 1984. “History of Freetown Music I”. Transcription of oral communication. Freetown. Unpublished.

- During, Chris. 1986. “History of Freetown Music II”. Transcription of oral communication. Freetown. Unpublished.

- Findlay, W.O. 1975. Forty Years of Broadcasting. A historical guide to the development of West Africa’s first Broadcasting Service. 59 pp. Freetown.

- Fyle, Clifford N. and Eldred D.Jones. 1980. A Krio-English Dictionary. Oxford

- Koroma, Salia. 1985. My Life Story. Interviewed by Heribert Hinzen. Stories and Songs From Sierra Leone, 5. People’s Educational Association of Sierra Leone, p. 8. Freetown.

- Nketia, J.H.. 1956. The Gramophone and Contemporary African Music in the Gold Coast. In: West African Institute of Social and Economic Research, Fourth Annual Conference. pp. 191-201.

- Report. 1969. of the Committee of Broadcasting Consultants on the Sierra Leone Radio and Sierra Leone Television Services and the Government Statement thereon. 25 pp. Freetown.

- Voss, Harald. 1962. Rundfunk und Fernsehen in Afrika. Köln

- Ware, Naomi Hooker. 1970. “Popular Musicians in Freetown”. In: African Urban Notes, No.4, 1970. pp. 11-18.

- Ware, Naomi. 1978. “Popular Music and African Identity in Freetown, Sierra Leone”. In: B.Nettle (ed.). Eight Urban Musical Cultures. Tradition and Change. pp. 296-320. Urbana.

- West African Review. 1947. “Variety Time at Freetown Radio”. West African Review, December 1947. pp. 1444-1445.

Appendix

Label Descriptions

Decca

The Decca numbers start with WA 726 but there are only a few numbers till the 900s where are more, in fact 45 of the 100. It continues only with WA 1653, WA 1703, 1709, 1863, 1925 and then again 2604, there are 20 within this 2600s. There are 8 in the 2700s, 25 in 3000s, 19 in the 3100s. There were in all 121 Decca shellacs Yellow Label in the SLBS library.

HMV

EMI had a number of labels with African music, and like Decca it is the colour of a labels wherebye we can distinguish them from each other. Mauve colour with GV letters is Ghana, as is the JLK in olive with numbers around 1100,of which 49 numbers are in Freetown. The JZ series, a yellow label too, is represented with only 14 records though the lowest number is 61 and the highest 6035. Have there really been over 6000 shellac discs from Ghana, Nigeria and Sierra Leone produced by HMV?

The ‘Red label’ by HMV covers Congo music with the letter mark LON. Possibly this is an indication that these discs have been taken over by the Loningisa company in the then Belgian Congo. LON are numbered in the 1000s and 1100s. In all there are from the 1000s 96 numbers, nearly complete. but from the the 1100s only 14 numbers.

Columbia

From the Columbia label we have in mauve 4 records with Congo Music – all in the 100s. There probably have been hundreds more as there was one disc numbered 540 in a private collection in Freetown. The letter mark says ESN an could like with LON also be an indication for a Congolese company supplying the recordings, this time it should be Esengo. A ‘Blue Columbia label’ with the mark GNT is there with the numbers 5, 6 and 10 all Sierra Leone music.

Philips

From Philips West African Records one single 78 is in the library, that is P 103 011 on a violet label.

Gallo

Gallo’s black Gallotone label identified with CO there are from the first 200 20 releases only. From GB the lowest number 1278 to 2680 there are 11 only, from GE 968 to 1161 only 4.There is music from Southern Africa and the South of the Congo.

Tropik

The yellow label with DC marking from 118 to 535 – 7 records only with music from Southern Africa and Nyasaland (today Malawi).

Hit Records

The white label from HIT Records is present with No. 75, 76, 79 and continues with a yellow label 90, 91, 97, 115-117, 119-121.

Troubadour

- The AFC series with a green colour label carries South African Music and starts with 167 and continues till 616 with 34 selected discs.

- Troubadour’s orange label BZ series is there with two numbers 6021 and 6023. The red label BZ series commences with 1107 and continues to 6145 with 21 discs of music from East and South Central Africa.

- The red label W Series from 100-122 with 15 records all from Nigeria. The WCB series starts with WCB 37 and continues till 48, besides WCB 43.

African Gramophone Stores

From the black and white label with AGS letters two numbers. 223 and 848, then with letters ROCK from 43 to 77 in all 9 discs. From the black and yellow label ‘Twist’ TT only no. 34. It is all East African music.

Ngoma

The Ngoma green and the red label records are with numbers from 379 to 2157 altogether 54.

Opika

The Lion label of Opika published Nigerian and Ghanaian music but in the SLBS collection there was only one number of the Opika label 2128, a Congolese band. Opika was a company for the Congo.

Nigerphone

Green and white label of Nigerphone from Nigeria is only present with a single example: NX 109.

Patsol

This record company from Calabar, Nigeria is here with a blue label and numbers PS 20 to PS 62 with six discs.

Queenophone

Queenophone from Ghana in a green and white label with only three numbers QP 119, 199, 246.

Senaphone

Senaphone with its dark lila label is there with FAO 1401, 1429, 1439

Melodisc

This label operating from London is there with numbers from 1311 to 1576 with only 12 discs.

Labels Operating Only In Sierra Leone During The 1950S And Early 1960S

Nugatone

- Adenuga & Jonathan’s Nugatone label appeared in several series with special colours going with them.

- The AA series with a green label is there from No. 47 to 71 with 12 records, the AA mauve label from 132 to 150 in four discs. The red label from AA 4 to 75 in 20 discs, the red and white from AA 5 to 131, 21 records. Within the AA series different colours were used but the numbering is only one, starting with AA 4 till AA 150.

- The AB series is there with the numbers 8 and 9 in an orange label.

- The BB label in mauve is 29 times represented, from 11 to 130.

- The Red label from BB 76 to BB 108 there are only 5. The white and black label starts with BB 2 and continues to BB 55 with 4 discs. Then the yellow label from BB 15 to BB 22 with 5 records. Here, like in the AA series, there is only one numbering with different colours, from BB 2 to 130 in all.

- The AB series in orange colour only in AB 8 and 9.

- The FA series in blue colour from FA 4 to FA 33 with 10 discs.

- The NU – Independence series is there from NU 1 to NU 111 with only 5 records.

- The Nugatone REL Black label records are documented with only a single disc REL 3.

- The RV series too is coloured in different shades, in black and blue and in white (test pressings). Starting with RV 1 to RV 35 there are 23 altogether.

- The SAL series in different colours again, in white, in yellow and in yellow and green from SAL 2 to SAL 15 only 4 discs.

Bassophone

The Bassophone blue label starts in the SLBS library with No. BS 22 to 223 with 16 records. The blue and white series with Nos. BS 149 and 221 , one red label with the no. BS 210. In white label from BS 41 to BS 206 in all 31 and the white and red label BS 3 to 117 5 and in yellow label one BS 39. The series are numerically one from BS 3 to 223.

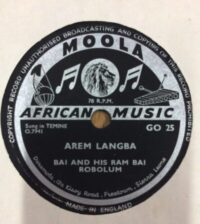

Moola-African Music

From Daramola the black label Moola is there with G.O. 41, 43, 45 and 46.

Rogie

From S .E. Roger’s label Rogie were only two records in the collection, i.e. R 3 and R 7. with a green label.

Lyrics ‘Welcome to The Queen’

Welcome Your Majesty, Elisabeth II

Welcome to loyal Sierra Leone

Welcome

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh

Welcome to loyal Sierra Leone

Welcome our precious Queen

Welcome a smiling you

Welcome Your Majesty, Elisabeth II

Welcome to loyal Sierra Leone

The link uniting us is very fortuned

spirified

Welcome Your Majesty, Elisabeth II

Welcome to loyal Sierra Leone

Happiness

God guide your visit well

We love gold and silver

and offer you the best of it

sunshine and love

Welcome our precious Queen

Welcome our smiling Duke

Welcome Your Majesty, Elisabeth II

Welcome to loyal Sierra Leone

WELCOME !!!

Notes

- The African Music Archives at Johannes Gutenberg Universität in Mainz.)

- A printed earlier version was published in 1994 as part of the Festschrift for Gerhard Kubik: Bender, Wolfgang 1994. “Farewell to the Queen. African Music on Shellac Discs: The Gramophone Library of the Sierra Leone Broadcasting Service.”in: August Schmidhofer und Dietrich Schüller. For Gerhard Kubik. Festschrift on the occasion of his 60th birthday. Frankfurt (Peter Lang). Vergleichende Musikwissenschaft Bd. 3. S. 219-244.

- As the Capital of Sierra Leone, Freetown has a 200 year history to look back upon. It was founded by English philanthropists in 1787 to repatriate liberated slaves of African origin. Even though this particular spot was not their real former home, it was at least in Africa. The early settlers were followed by so called ‘recaptives’ – which were liberated from slave ships by the Royal Navy. In 1792 the Nova Scotians arrived from North America and in 1800 Maroons from Jamaica. A new society evolved out of this conglomeration under British tuition and later colonial rule.

Nevertheless a lot of the pecularities of each group of settlers

were retained to some extent and contributet to a colourful variety. - cf. David Rycroft, “The Guitar Improvisations of Mwenda Jean Bosco”, in: African Music, Vol. 2, No.4, 1961, pp. 81-98 “For his Masanga recording Bosco was later to gain first prize under the Osborn Awards for the best African music of the year (1952).” p. 81.

- John Collins and Paul Richards, “Popular Music in West Africa – Suggestions For an Interpretative Framework”, in: David Horn, Philip Tagg (eds.), Popular Music Perspectives, Göteborg and Exeter, 1982, pp. 111-141.

- It is absolutely neccessary that more detailed studies of this area of production are undertaken. A good example is the recently published study by Flemming Harrev on the East African Records Ltd. Company in Nairobi. Until then one could speculate or base arguments on speculations and will now be proved wrong or right. Definitely many arguments brought forward earlier are since this study no longer tenable. Studies of musical developments in East Africa have to be reconsidered now with this available information.

- According to Chris During 1984, Adenuga sang also on Nugatone RV 22, ‘Repete’, and on Nugatone Best 1.

- cf. W. Bender, Calender – An Appraisal, in: Bayreuth African Studies No. 9, W. Bender (ed.) Perspectives on African Music, 1989, pp. 43-68.