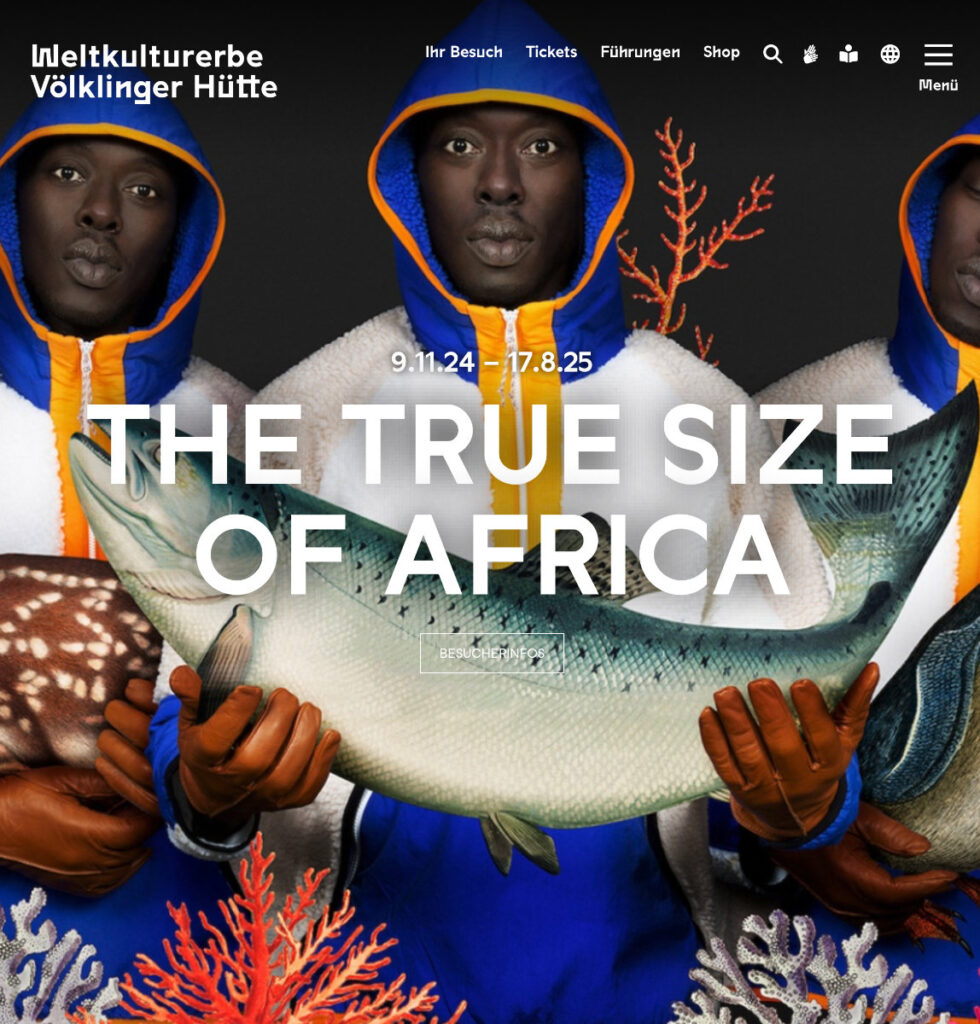

Die Welterbestätte unter dem Generaldirektor Dr. Ralf Beil hat sich Großes vorgenommen.

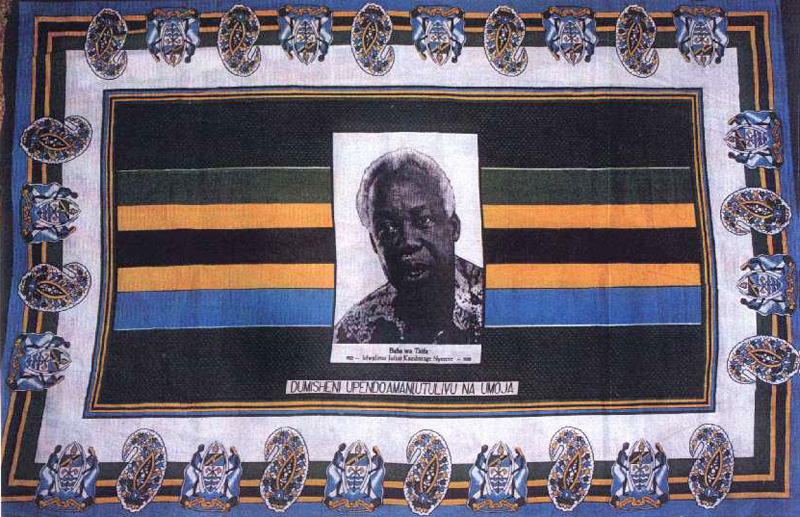

Die Ausstellung THE TRUE SIZE OF AFRICA erprobt Annäherungen, die Denktraditionen, Vorurteile und Stereotypen aufspüren und neue Sichtweisen ermöglichen – mittels Kulturgeschichte und Gegenwartskunst, durch stetige Perspektivwechsel und künstlerische Vielstimmigkeit. Ein hochgestecktes Ziel. Ob es funktioniert wird sich schwer nachweisen lassen. Wie bei allen anspruchsvollen Ausstellungen dieser Art wird sehr viel angeboten, aber ob die Vielfalt der eingesetzten Medien genutzt wird? Zweifel sind angebracht. Beim Besuch konnte ich beobachten, daß nur Wenige den „Mediaguide“ nutzten. Kinder, Jugendliche, erfahren mit der modernen Technik, hörten sich die Musik passend zu den Bildern auf den Monitoren an. Nicht immer erschien auf dem „Mediaguide“ die gerade passende Information. An den Vitrinen waren, klassisch, „Legenden“ angebracht, aber nur mit den minimalen Informationen. Vom Aufbau her also keine textlastige Präsentation. Ohne die zusätzlichen Inhalte auf dem „Mediaguide“, allerdings, erschließt sie sich nicht.

Continue reading “THE TRUE SIZE OF AFRICA. Ausstellung in der Welterbestätte Völklinger Hütte”